相關商品

商品簡介

作者簡介

目次

書摘/試閱

商品簡介

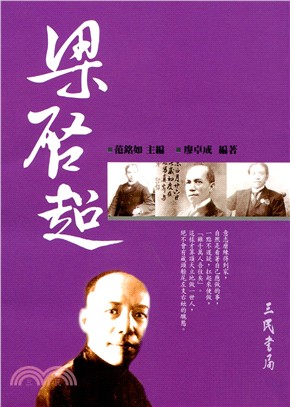

This was the motto of Chang Kuo-sin, and the ideal which he inspired generations of students of communication to follow. He proved his own dedication to this when, in 1949, he found himself in Nanking, the former nationalist capital, under the rule of the newly victorious communists. For eight months he lived and attempted to work in the midst of these historical changes. He managed to smuggle his detailed notes out to share with the world at a time when almost no reports of the new regime were being published. To mark the centenary of his birth, Hong Kong Baptist University’s School of Communication has republished this important work by one of its most distinguished professors.

作者簡介

CHANG Kuo Sin (1916–2006) worked as a translator, a reporter, a film-maker, an author, a professor and the head of the Communication Department of the Hong Kong Baptist College. He lived through some of the most turbulent times of the twentieth century and bore witness, with his characteristic devotion to the truth, to some of the defining events of our times.

目次

PART ONE

Communists Rule in Nanking After One Month of Trial

(April 23 – May 23, 1949)

1. Communist Government

2. Popular Reactions

3. Communist Press

4. The Communist Army

5. Nationalist Retreat from Nanking

6. Communists and Foreign Recognition

PART TWO

Communist Rule in China After Eight Months of Trial

(April – December 1949)

1. Communist Totalitarianism

2. Communist Efforts to Disguise Totalitarianism

3. Democratic Spirit Within the Communist Party

4. The Threat of Diversionism Inside the Communist Party

5. Communist “Lean to One Side” Principle

6. The Merits and Demerits of the Communist Government

7. Disillusionment and Discontent in Communist China

8. Causes of Disillusionment and Discontent

9. Disillusionment and Discontent Among Workers

10. Disillusion and Discontent Among Farmers

11. Problems Facing the Communists – Currency

12. Problems Facing the Communists – Agriculture and the Industry

13. Problems Facing the Communists – Famine

14. Problems Facing the Communists – How to Sell Soviet Russia to the Chinese People

15. Soviet Help in the Sovietisation of China

16. Soviet Russians and Manchuria

17. Moslem Opposition to Communist Rule

18. Foreigners in Communist China

19. “Democratic Personages” in Peking

20. Will the Communists Turn Titoists in the Future?

21. Farewell to Communist China

Communists Rule in Nanking After One Month of Trial

(April 23 – May 23, 1949)

1. Communist Government

2. Popular Reactions

3. Communist Press

4. The Communist Army

5. Nationalist Retreat from Nanking

6. Communists and Foreign Recognition

PART TWO

Communist Rule in China After Eight Months of Trial

(April – December 1949)

1. Communist Totalitarianism

2. Communist Efforts to Disguise Totalitarianism

3. Democratic Spirit Within the Communist Party

4. The Threat of Diversionism Inside the Communist Party

5. Communist “Lean to One Side” Principle

6. The Merits and Demerits of the Communist Government

7. Disillusionment and Discontent in Communist China

8. Causes of Disillusionment and Discontent

9. Disillusionment and Discontent Among Workers

10. Disillusion and Discontent Among Farmers

11. Problems Facing the Communists – Currency

12. Problems Facing the Communists – Agriculture and the Industry

13. Problems Facing the Communists – Famine

14. Problems Facing the Communists – How to Sell Soviet Russia to the Chinese People

15. Soviet Help in the Sovietisation of China

16. Soviet Russians and Manchuria

17. Moslem Opposition to Communist Rule

18. Foreigners in Communist China

19. “Democratic Personages” in Peking

20. Will the Communists Turn Titoists in the Future?

21. Farewell to Communist China

書摘/試閱

I began my life behind the Bamboo Curtain on April 23, 1949, the day the nationalists pulled out of Nanking. “Bamboo Curtain” is a term coined by the American press

for the totalitarian rule which the Chinese communists are expected to establish in China.

“Bamboo Curtain”, in my opinion, is a more appropriate term for China than “Iron Curtain”, which is used in reference to Soviet Russia, because the barrier against the

outside world would not be as tight as that erected by Soviet Russia, due to the long vulnerable Chinese coastline and the large Chinese population abroad.

Another meaning of the Bamboo Curtain is that people behind a bamboo curtain can see outside the curtain, but people outside cannot see inside. This is generally presumed

to be what the Chinese communists and communists in other countries are doing – banning foreign observation and inspection of their country, while maintaining a

gigantic information or espionage network in other countries.

The most remarkable thing that emerged after the “liberation” of Nanking was the ingenuity and scale of the communist underground network. The set-up of

the nationalist political and economic nerve centre was infested with the virus of communist espionage and sabotage, covering every part and level of the governmental

machinery and reaching deep even into the Army Headquarters. This was one of the causes of the fast disintegration of Chiang Kai-shek’s power. One communist underground agent told me there were eight thousand underground workers in Nanking. He said three thousand of them were members of the Communist

Party. Others were members of anti-Kuomintang parties and factions, communist sympathisers, individual political opportunists and people who were disgusted with the

Kuomintang government. His figure may be a little exaggerated, but in my opinion it is pretty near to the truth.

Some of the underground agents were high up and deep in the most vital and confidential branches of the nationalist government. Some started their career in the

civil service immediately after they left college and after going through the normal spell of training set up by the Kuomintang. Little wonder that all the secrets of the

nationalist government were known to the communists before they were locked in the safety box. In Nanking, whenever the Garrison Headquarters drew up a blacklist

of names for a nocturnal police round-up, the communist underground always had the list before the police were informed of it.

During the peace negotiations in Peking in April 1949, nationalist peace delegate General Liu Fei insisted to chief communist peace delegate Chou En-lai, now Premier of the Central People’s Government, that the nationalist army totalled over four million men and could still fight if the communists refused to accede to their peace proposals.

Premier Chou En-lai smiled and took a piece of paper from his drawer and showed it to General Liu. That piece of paper contained the most detailed information on the

disposition of all the remaining nationalist units with the names of even the battalion commanders. The paper gave the total strength of the remnant nationalist army as 1.1

million. General Liu, according to the communist sources who gave me the story, “reddened with embarrassment” and said, “Well, our payroll shows over four million men”. After the nationalist army pulled out of Nanking, communist underground agents immediately revealed their identity and quietly went on to take over governmental offices and property. The chief reporter, Mr. Li Kuo, and several typesetters in the Kuomintang party organ, Central Daily News, announced their identity in a meeting of the paper’s staff on April 23 and formed a committee for

checking and taking over the paper’s plant. In the Central News Agency, eight members of its staff emerged as communists.

Two editors of the Military News Agency (operated by the Nationalist Defence Ministry), who had access to all of the war and intelligence reports of the Ministry’s G-2 Department, turned out to be members of Marshal Li Chisen’s Kuomintang Revolutionary Committee. Even the confidential secretary of the Chief of G-3

Department of the Nationalist Defence Ministry, Captain Huang, was a communist. He had obtained his commission after a period of training in a Kuomintang military

academy and was given the important position because of his “loyal” service.

As the confidential secretary of the G-3 Chief, Captain Huang handled all of the top-secret documents concerning military operations, defence plans, and troop deployment.

When the Defence Ministry was making preparations to move out of Nanking a few days before the fall of the city, he quit the Ministry – but not before stealing topsecret

military maps of defence works and strategic areas in Taiwan.

At the end of May 1949, I wrote a series of six articles for the United Press on how communist rule had affected the common man in Nanking after a period of one month.

These six articles are reproduced here without any change as the first portion of my report on communist rule.

for the totalitarian rule which the Chinese communists are expected to establish in China.

“Bamboo Curtain”, in my opinion, is a more appropriate term for China than “Iron Curtain”, which is used in reference to Soviet Russia, because the barrier against the

outside world would not be as tight as that erected by Soviet Russia, due to the long vulnerable Chinese coastline and the large Chinese population abroad.

Another meaning of the Bamboo Curtain is that people behind a bamboo curtain can see outside the curtain, but people outside cannot see inside. This is generally presumed

to be what the Chinese communists and communists in other countries are doing – banning foreign observation and inspection of their country, while maintaining a

gigantic information or espionage network in other countries.

The most remarkable thing that emerged after the “liberation” of Nanking was the ingenuity and scale of the communist underground network. The set-up of

the nationalist political and economic nerve centre was infested with the virus of communist espionage and sabotage, covering every part and level of the governmental

machinery and reaching deep even into the Army Headquarters. This was one of the causes of the fast disintegration of Chiang Kai-shek’s power. One communist underground agent told me there were eight thousand underground workers in Nanking. He said three thousand of them were members of the Communist

Party. Others were members of anti-Kuomintang parties and factions, communist sympathisers, individual political opportunists and people who were disgusted with the

Kuomintang government. His figure may be a little exaggerated, but in my opinion it is pretty near to the truth.

Some of the underground agents were high up and deep in the most vital and confidential branches of the nationalist government. Some started their career in the

civil service immediately after they left college and after going through the normal spell of training set up by the Kuomintang. Little wonder that all the secrets of the

nationalist government were known to the communists before they were locked in the safety box. In Nanking, whenever the Garrison Headquarters drew up a blacklist

of names for a nocturnal police round-up, the communist underground always had the list before the police were informed of it.

During the peace negotiations in Peking in April 1949, nationalist peace delegate General Liu Fei insisted to chief communist peace delegate Chou En-lai, now Premier of the Central People’s Government, that the nationalist army totalled over four million men and could still fight if the communists refused to accede to their peace proposals.

Premier Chou En-lai smiled and took a piece of paper from his drawer and showed it to General Liu. That piece of paper contained the most detailed information on the

disposition of all the remaining nationalist units with the names of even the battalion commanders. The paper gave the total strength of the remnant nationalist army as 1.1

million. General Liu, according to the communist sources who gave me the story, “reddened with embarrassment” and said, “Well, our payroll shows over four million men”. After the nationalist army pulled out of Nanking, communist underground agents immediately revealed their identity and quietly went on to take over governmental offices and property. The chief reporter, Mr. Li Kuo, and several typesetters in the Kuomintang party organ, Central Daily News, announced their identity in a meeting of the paper’s staff on April 23 and formed a committee for

checking and taking over the paper’s plant. In the Central News Agency, eight members of its staff emerged as communists.

Two editors of the Military News Agency (operated by the Nationalist Defence Ministry), who had access to all of the war and intelligence reports of the Ministry’s G-2 Department, turned out to be members of Marshal Li Chisen’s Kuomintang Revolutionary Committee. Even the confidential secretary of the Chief of G-3

Department of the Nationalist Defence Ministry, Captain Huang, was a communist. He had obtained his commission after a period of training in a Kuomintang military

academy and was given the important position because of his “loyal” service.

As the confidential secretary of the G-3 Chief, Captain Huang handled all of the top-secret documents concerning military operations, defence plans, and troop deployment.

When the Defence Ministry was making preparations to move out of Nanking a few days before the fall of the city, he quit the Ministry – but not before stealing topsecret

military maps of defence works and strategic areas in Taiwan.

At the end of May 1949, I wrote a series of six articles for the United Press on how communist rule had affected the common man in Nanking after a period of one month.

These six articles are reproduced here without any change as the first portion of my report on communist rule.

主題書展

更多主題書展

更多書展本週66折

您曾經瀏覽過的商品

購物須知

為了保護您的權益,「三民網路書店」提供會員七日商品鑑賞期(收到商品為起始日)。

若要辦理退貨,請在商品鑑賞期內寄回,且商品必須是全新狀態與完整包裝(商品、附件、發票、隨貨贈品等)否則恕不接受退貨。