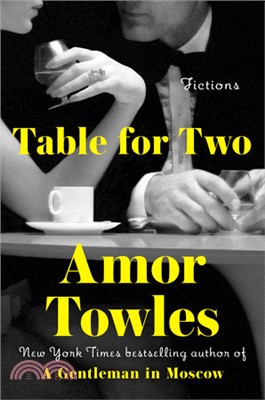

Goliath

商品資訊

ISBN13:9780312675011

替代書名:Goliath

出版社:St Martins Pr

作者:Susan Woodring

出版日:2012/04/24

裝訂/頁數:精裝/360頁

規格:22.2cm*14.6cm*3.2cm (高/寬/厚)

商品簡介

作者簡介

名人/編輯推薦

書摘/試閱

相關商品

商品簡介

"Goliath is a careful, contemplative study of the rhythms of collective grief. Woodring's sense of the constraints and hard-earned pleasures of home rings as true and pure as a train whistle in the night."—Michael Parker, author of A Watery Part of the World

When fourteen-year-old Vincent Bailey stumbles upon the body of Percy Harding, Goliath’s most important citizen, near the railroad tracks one perfect autumn afternoon, the tragic death seems literally unbelievable: how could it have been a suicide? Only Harding’s secretary, Rosamond, might have had a glimmer, but that glimmer just tugs at her, urges her to find out more. Harding isn’t the first person to leave Rosamond: everybody does, from her husband Hatley, who walked out on her years ago; to her complicated daughter Agnes, whose girlhood bedroom was papered with the maps of the places she wanted to escape to. Brought to life by a cast of characters as varied and rich as in any fiction—from Clyde Winston, the town’s police chief, to Goliath’s self-taught preacher Ray to Percy Harding’s unmoored widow Lela—Goliath’s appeal is as memorable as Elizabeth Strout’s Crosby, Maine, or Richard Russo’s Empire Falls.

When fourteen-year-old Vincent Bailey stumbles upon the body of Percy Harding, Goliath’s most important citizen, near the railroad tracks one perfect autumn afternoon, the tragic death seems literally unbelievable: how could it have been a suicide? Only Harding’s secretary, Rosamond, might have had a glimmer, but that glimmer just tugs at her, urges her to find out more. Harding isn’t the first person to leave Rosamond: everybody does, from her husband Hatley, who walked out on her years ago; to her complicated daughter Agnes, whose girlhood bedroom was papered with the maps of the places she wanted to escape to. Brought to life by a cast of characters as varied and rich as in any fiction—from Clyde Winston, the town’s police chief, to Goliath’s self-taught preacher Ray to Percy Harding’s unmoored widow Lela—Goliath’s appeal is as memorable as Elizabeth Strout’s Crosby, Maine, or Richard Russo’s Empire Falls.

作者簡介

SUSAN WOODRING grew up in Greensboro, North Carolina. Her previous publications are a first novel, The Traveling Disease, and Springtime On Mars: Stories. She has been published in Passages North and a variety of other literary publications. She won the 2006 Isotope Editor's Prize, has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize, and was a notable mention in Best American Short Stories 2010.

名人/編輯推薦

"Like a contemporary Winesburg, Ohio, Susan Woodring's Goliath brings small town life beautifully, achingly alive. Sprinkled with marching bands, baseball, and parades, and a cast of southern characters who will charm the pants off you, Goliath is a memorable novel, written in a new memorable voice."—Ann Hood, author of The Knitting Circle

"Woodring's writing is so clear and moving that the reader often feels, as she says of about one of her characters, as if 'the world had been sucked clear of true sound.' This beautiful portrait of a place and its people, rendered so quietly and intimately, shuts out the world outside its pages as you read. Only the best novels can make you forget yourself as reader. Goliath is the kind of book you don't want to put down or to end."--Brad Watson, author of The Heaven of Mercury

"Woodring's writing is so clear and moving that the reader often feels, as she says of about one of her characters, as if 'the world had been sucked clear of true sound.' This beautiful portrait of a place and its people, rendered so quietly and intimately, shuts out the world outside its pages as you read. Only the best novels can make you forget yourself as reader. Goliath is the kind of book you don't want to put down or to end."--Brad Watson, author of The Heaven of Mercury

書摘/試閱

A teenage boy coming in from a morning of lighting fires along far-flung creeks was the one to find the body. He stopped shock-still, uncertain of what he saw splayed out there on the mud. But the clean white sunlight shone down on it same as it did on the bent weeds and the grass-and rock-stubble field leading up a hill, across a gravel path littered with junk parts and gutted automobiles set on cinder blocks, a white box of a house beyond. What he saw was true. A handful of blackbirds flung themselves up at the sky, crossed over in a shifting amoeba, and lit on a telephone wire, strung over the highway beyond the house. The boy stood looking down the set of silver railroad tracks glaringly bright in the sunshine. The sky above him was made of color so thick, it seemed he could plunge his open hand into its blueness.

He came back to himself and turned, hurrying across the field. The boy, Vincent Bailey, did not feel his feet move over the uneven earth and the bulging roots of old trees. All he could pay mind to was his heart thudding hard against his rib cage and the rush of air coming in and out through his lungs. He reached the house and stepped inside, the screen door clattering shut behind him. His father was in the living room, watching television with a plate of scrambled eggs balanced on his lap.

Vincent told him what he had found. "It's Percy Harding," he said.

His father set his plate aside, slow to believe. "Are you sure?"

Vincent was certain, and his father moved to the kitchen telephone to summon the police. They went out front to wait. His father did not speak, though he watched the boy in silhouette, then turned his eyes to the bend of road where the squad car would arrive. Vincent stared into the sun until it smeared purple when he blinked.

Some moments later, a patrol car and an ambulance sloped down the long gravel drive to where Vincent and his father stood. Neither vehicle had its siren turned on, and, to Vincent, it seemed the world had been sucked clean of true sound. Even when his father spoke to him, he just saw the movement of his father's lips beneath his eyes squinting in the sun. The three men-Vincent's father, the police chief of Goliath, and the coroner-nodded at one another and then turned to Vincent, who led them out to the field.

He worried the body would be gone, mysteriously up and left, but they came to it directly, and it was worse now, even more still, as if it were possible for a person to grow more dead in a half hour's time. Though it was the beginning of October, the air felt as mild and new as on a spring day.

The boy stood back with his father, who folded his arms across his chest and leaned over to spit into the mud. The police chief, a patient, solid, grim-faced man who was slow in his movements, and the coroner, a pudgy fellow with a wide forehead that beaded with sweat despite the cool breeze riding across the trees, spoke quietly over the body. It was quickly determined that the deceased, struck by the train, was Percy Harding, just as Vincent had reported. His father stepped forward to hazard a closer look but kept his expression hard. Vincent, wanting the relief he had expected to feel when the situation was safely in the hands of the police, kept his eyes turned away from his father's. He searched the sky for more blackbirds.

Later, after the body was taken away and the men had left, Vincent sat at the kitchen table with a supper of cornbread and beans, ladled off the stove by his mother. She and Vincent's sisters had just returned from morning church services, and she was still dressed in pressed pink linen, a summer dress. She set the plate down and lingered a moment, her hand on his shoulder. The girls, all older than Vincent, fluttered about the kitchen, hoping to catch the details of what Vincent had found. Finally their mother shooed them away, and Vincent was left alone with his father, who sat across from him and looked from his own plate to his son to the window.

"It's going to be a hard thing to forget," he said. "What we saw today."* * *

The Baileys lived in a ripple of wooded hills threaded with county roads a few miles west of the town of Goliath, where Percy Harding had lived and presided over Harding Furniture Company and where Vincent Bailey, riding the county school bus, had just begun attending high school. There in town it had been a blessedly ordinary summer of modest white nuptials and giant insects and bloated afternoons spent in kiddie pools and backyards, the neighborhoods of Goliath filling with the greasy smells of charred meat and bug repellent. During these months, the heat saturated Goliath and the people sat behind electric fans set on front porches, the ladies' hair tied back in bandannas. They passed around garden tomatoes, which grew heavy and red on their vines all the way through the end of September.

They weren't prepared for the sad news when Vincent Bailey found it on the first Sunday of October, the weather just beginning to cool. The sorrow of it went out in glittering gusts like the old-fashioned purple and pink insecticide clouds sprayed through the streets in years past. There was a sheen to a tragedy this grave, this mysterious. It began with Clyde Winston, the soon-to-retire police chief, going out to inform the widow.

Clyde left the Baileys' house after the body was removed and drove into Goliath, passing the two-pump gas station, the huge gray rectangle of the Harding Furniture Factory, the railroad tracks, the downtown shops, the post office, and the great white Baptist church. Beyond the church, the roads split into narrow neighborhood streets with cracked sidewalks and gray and blue houses hunched over splintered front porches.

The Harding house was a monstrous brick structure sitting atop a hill looking over the residential end of Main Street. The gentle slopes of the Goliath Cemetery-just a few graves shy of full capacity-lay across the street. The house was reached by a private graveled avenue labeled Redemption Lane. A long driveway led up the sparsely treed hill and came to a semicircle a few steps from the heavy wood door, flanked on both sides by intricate stained glass, vine- and leaf-patterned. Years ago, factory workers, called there by Martha Harding, the namer of the private lane and the factory president's wife during the post-World War II years, had stood waiting in that same spot. They had been called there for a prayer meeting, which Martha herself administered from her leather chesterfield inside.

Lela Harding, Percy's wife, opened the door clutching a glass of amber-colored liquid, slender ice cubes floating on top. She was a petite woman with glossy black hair and a powdery-white complexion. Clyde Winston pronounced the news, disclosing as few details as possible. "No," she said, shaking her head. "No." She stood motionless for a moment, then turned and stepped into the house, and Clyde, after a moment's hesitation, followed her.

"I was just about to take the car out," she said.

Clyde was unsure of what to do or say to console her. They sat without speaking a space apart on a thickly upholstered sofa in a room made of shining brass and gleaming old furniture. She drank and touched her face with her fingertips. Her husband had been the most powerful and the most beloved man in town, but Lela had mostly kept to herself. Few knew her well. The music, a far-off radio, changed from song to song, back to the announcer, back to song. When her glass was empty, Lela held it up to Clyde to refill, gesturing to an unlocked cabinet where he found the bourbon. Returning her refreshed glass, he sat next to her on the couch and she bent a tiny bit closer to him. He thought of Martha Harding, whom he had seen only at her viewing-she was hollow-looking, carefully embalmed. It was the first dead person young Clyde, then fifteen years old, had ever seen.

"It's too big. It's like driving a bus."

"Ma'am?"

She looked at him. "He must have left early," she said. "I was still asleep."

The elevator music continued, interrupted again by the announcer's lilting voice. Clyde did not argue with Lela, but instead let her sit there and come to understanding. She closed her eyes, and he began to move his hand up and down her back. At another time the gesture might have seemed too familiar. Now, though, in the moment of her stark grief, her drinking, the awful, shapeless music, this seemed the only thing for Clyde to do. He was a widower, ten years on his own now, and was unpracticed in the art of offering sympathy. His palm moved slowly against the small knots of vertebrae and Lela Harding seemed more fragile with each passing.

She touched her temples. "I wish we'd get some rain."

Clyde left after dark, the radio still playing, and unwilling to return home, looped the streets of town and the outlying county roads until dawn. He drove past his son's trailer, in the woods behind the school, past his neighbors' houses, past the factory. The downtown shops were silent and dark except for the soft buzzing of the streetlights and the perennial blue glow of the Pepsi fountain inside the Tuesday Diner.

* * *

The body was brought to Thompson's Funeral Home, and in the morning, Holland Thompson, the undertaker, set about preparing it for internment. Holland was a slow, methodical man who would have been a surgeon except he preferred a cleaner, more exact succession of tasks. He worked alone in a room furnished with only the table and his instruments, the cabinet, the industrial sink, and a portable radio tuned to a station that played covers of old pop songs. His married, childless daughter Celeste came, knocked shortly on the door, and then opened it without invitation. Her father, irritated at the interruption, turned sharply to her, and though Percy Harding was barely recognizable in his mangled state, she knew at once who it was laid out there on the cold steel table.

She gasped. Though the daughter of a mortician, she had never seen such a corpse. The body was so completely dead-simply emptied of life-and yet so untouched. His skin had not yet turned waxy and unreal, and he wasn't terribly bloody. Instead, the body was rumpled, a misshapen scattering of broken bones sealed over by skin and a blue jogging suit.

"It was a train," Holland said unnecessarily-Celeste had already heard what had happened, indeed had been the one to answer the phone. She had known Percy Harding, now dead, was coming to them. Her father shook his head over the particular violence of the tragedy, the degree of technical skill his job now required of him. He turned to his cabinet to select a thin, sharp needle and a spool of wire. He gestured to his daughter with a pair of surgical scissors.

"You keep this to yourself," he said.

"All right," she said, and hurried out.

She was still clutching her car keys when she whispered her discovery to the checkout girl at Lucky Grocery. "One hundred percent crushed," Celeste told her.

The checkout girl, a can of green beans in her hand, stopped, looking up at Celeste. The buyer of the green beans, a woman with two small children at her knees, asked, "What did you say?" though she'd heard Celeste well enough. She picked up the littler of her two boys and listened: Celeste, in a whisper, described what she had seen.

The news began swirling out, Celeste and the checkout girl and then the mother of the little boys and the bag boy all speaking of it there at the front of the store. Of course many had already heard that Percy Harding had died-it was in the local papers-but few had spoken to someone who had actually seen the body. Celeste repeated again and again, "One hundred percent crushed," and nodded at the blank faces, their brows wrinkled, their mouths half forming questions as the image settled in. Those coming in and those leaving heard and lingered; with time, a murmuring knot collected there. There were shoppers who had come off third shift a few hours earlier: the women still had their hair tied back. The men had their work boots on. Some were off work this morning, come in blue jeans and sweatshirts to pick up groceries for tonight's supper, and a few were in dressy slacks and sweater vests, late for their office jobs, dropping by to pick up coffee and pastries for their coworkers. They listened to Celeste describe what she had seen, and they began to understand: Percy Harding had been struck-destroyed-by a train.

The shock and sorrow of it clung to them as they stood by the automatic sliding glass doors, too numb to move. After a time, though, they remembered themselves and started to leave, some with thoughts of going to retrieve their children early from school, some to wait for the day-shift workers to come down the hill from the factory at four, and some to go home and sort it out, this horrible thing that had happened here, in their own small realm of church, friends, and work. Each recollected an actual encounter with the man, or at the very least, a sighting, and those remembered moments were absorbingly macabre now. The people recalled what they could of Percy Harding and looked, through time passed, for some foretelling, some hint, of the present disaster.

"He was a rock," one worker told another, and they both nodded. It was true-Percy Harding had been the town's single greatest support-but this was also the beginning of the kinds of legends people create after a passing.

"Harding will never be the same. We will never be the same," another said.

"It's true, it's true," came a response.

They referred to the incident as an accident, though many went home to confront their loved ones with the chilling uncertainty as to how a man might be struck by a train without either lying down for it or else standing resolutely on the tracks. People speculated. One man recalled a scene in a movie where a woman's shoe got wedged between the ground and the rail and the woman had struggled to free herself in time.

Clyde Winston stopped by the post office on his way home from the station late that afternoon. Hearing one of his neighbors speak of Percy's death, relaying a description, largely distorted, of the condition he was found in, he remembered the granite look of Lela Harding's eyes, how fragile the bones in her back had felt under his hand. From the post office, he went to his son's mobile home behind the junior high school rather than return to his own dark cave of a house. He leaned against the kitchen sink with a tepid glass of water and said, "It just don't make sense." He took a drink, shook his head, and said again, "It just don't."

"You're right there," his son agreed. "A man does not stand in the way of a train unless he means to get hit." He was still a moment, thinking, watching his father. "Or unless he's crazy," he added. He stood gripping the back of a kitchen chair, opening and closing his fingers to ease the tension in his knuckles. Ray Winston was a large man, his sturdy limbs and broad chest in proportion to his more than six feet of height. He wore his curly brown hair longish, just over the collar of his county-issued work shirt. In a softer tone, he continued, "And no one even guessing at it, not even knowing he was capable of it."

The two were quiet for a moment, considering the dead man's intentions. A chill breeze seeped through the slipshod hinges of the aluminum trailer even as sunshine beat through the uncurtained windows, lighting up dirt smudges here and there across the pane. Ray Winston was the groundskeeper for the county, mostly keeping up the yard of the junior high and high school, built on neighboring lots, and the grade schools across the way. He was also a part-time preacher, ordained by the power of the Spirit and none other, bringing the good news to the poor, the downtrodden. He kept his own worldly load light. He belonged to no church and did not do his preaching while lounging on a leather chesterfield in a great house on a hill, but instead stood on the doorsteps of Goliath, visiting the physically ill and the spiritually unwell. Now, also unlike Martha Harding, he kept his silence, waiting to see what else Clyde needed to say. He had learned that much-the ministry of listening-from his father.

Clyde had served the town of Goliath for decades. He had dealt with any number of domestic squabbles, drunken insanities, and break-ins. There had also been acts of vandalism, fits of meanness, and episodes of blatant stupidity. He had seen other suicides. But there was something different in this one. It was as if every person in town had put their own bodies in way of the train and were all broken now, spiritless.

After a moment, Clyde set his glass down and spoke.

"A person goes that far," he said, "he takes the rest of us partway with him." He stared squarely into his son's eyes. "You can't unsee a thing like that, you can't unlive it."

Vincent didn't answer. Outside, the clouds swept across the sky in quick-time, blossoming orange, then pink, then blue gray.

He came back to himself and turned, hurrying across the field. The boy, Vincent Bailey, did not feel his feet move over the uneven earth and the bulging roots of old trees. All he could pay mind to was his heart thudding hard against his rib cage and the rush of air coming in and out through his lungs. He reached the house and stepped inside, the screen door clattering shut behind him. His father was in the living room, watching television with a plate of scrambled eggs balanced on his lap.

Vincent told him what he had found. "It's Percy Harding," he said.

His father set his plate aside, slow to believe. "Are you sure?"

Vincent was certain, and his father moved to the kitchen telephone to summon the police. They went out front to wait. His father did not speak, though he watched the boy in silhouette, then turned his eyes to the bend of road where the squad car would arrive. Vincent stared into the sun until it smeared purple when he blinked.

Some moments later, a patrol car and an ambulance sloped down the long gravel drive to where Vincent and his father stood. Neither vehicle had its siren turned on, and, to Vincent, it seemed the world had been sucked clean of true sound. Even when his father spoke to him, he just saw the movement of his father's lips beneath his eyes squinting in the sun. The three men-Vincent's father, the police chief of Goliath, and the coroner-nodded at one another and then turned to Vincent, who led them out to the field.

He worried the body would be gone, mysteriously up and left, but they came to it directly, and it was worse now, even more still, as if it were possible for a person to grow more dead in a half hour's time. Though it was the beginning of October, the air felt as mild and new as on a spring day.

The boy stood back with his father, who folded his arms across his chest and leaned over to spit into the mud. The police chief, a patient, solid, grim-faced man who was slow in his movements, and the coroner, a pudgy fellow with a wide forehead that beaded with sweat despite the cool breeze riding across the trees, spoke quietly over the body. It was quickly determined that the deceased, struck by the train, was Percy Harding, just as Vincent had reported. His father stepped forward to hazard a closer look but kept his expression hard. Vincent, wanting the relief he had expected to feel when the situation was safely in the hands of the police, kept his eyes turned away from his father's. He searched the sky for more blackbirds.

Later, after the body was taken away and the men had left, Vincent sat at the kitchen table with a supper of cornbread and beans, ladled off the stove by his mother. She and Vincent's sisters had just returned from morning church services, and she was still dressed in pressed pink linen, a summer dress. She set the plate down and lingered a moment, her hand on his shoulder. The girls, all older than Vincent, fluttered about the kitchen, hoping to catch the details of what Vincent had found. Finally their mother shooed them away, and Vincent was left alone with his father, who sat across from him and looked from his own plate to his son to the window.

"It's going to be a hard thing to forget," he said. "What we saw today."* * *

The Baileys lived in a ripple of wooded hills threaded with county roads a few miles west of the town of Goliath, where Percy Harding had lived and presided over Harding Furniture Company and where Vincent Bailey, riding the county school bus, had just begun attending high school. There in town it had been a blessedly ordinary summer of modest white nuptials and giant insects and bloated afternoons spent in kiddie pools and backyards, the neighborhoods of Goliath filling with the greasy smells of charred meat and bug repellent. During these months, the heat saturated Goliath and the people sat behind electric fans set on front porches, the ladies' hair tied back in bandannas. They passed around garden tomatoes, which grew heavy and red on their vines all the way through the end of September.

They weren't prepared for the sad news when Vincent Bailey found it on the first Sunday of October, the weather just beginning to cool. The sorrow of it went out in glittering gusts like the old-fashioned purple and pink insecticide clouds sprayed through the streets in years past. There was a sheen to a tragedy this grave, this mysterious. It began with Clyde Winston, the soon-to-retire police chief, going out to inform the widow.

Clyde left the Baileys' house after the body was removed and drove into Goliath, passing the two-pump gas station, the huge gray rectangle of the Harding Furniture Factory, the railroad tracks, the downtown shops, the post office, and the great white Baptist church. Beyond the church, the roads split into narrow neighborhood streets with cracked sidewalks and gray and blue houses hunched over splintered front porches.

The Harding house was a monstrous brick structure sitting atop a hill looking over the residential end of Main Street. The gentle slopes of the Goliath Cemetery-just a few graves shy of full capacity-lay across the street. The house was reached by a private graveled avenue labeled Redemption Lane. A long driveway led up the sparsely treed hill and came to a semicircle a few steps from the heavy wood door, flanked on both sides by intricate stained glass, vine- and leaf-patterned. Years ago, factory workers, called there by Martha Harding, the namer of the private lane and the factory president's wife during the post-World War II years, had stood waiting in that same spot. They had been called there for a prayer meeting, which Martha herself administered from her leather chesterfield inside.

Lela Harding, Percy's wife, opened the door clutching a glass of amber-colored liquid, slender ice cubes floating on top. She was a petite woman with glossy black hair and a powdery-white complexion. Clyde Winston pronounced the news, disclosing as few details as possible. "No," she said, shaking her head. "No." She stood motionless for a moment, then turned and stepped into the house, and Clyde, after a moment's hesitation, followed her.

"I was just about to take the car out," she said.

Clyde was unsure of what to do or say to console her. They sat without speaking a space apart on a thickly upholstered sofa in a room made of shining brass and gleaming old furniture. She drank and touched her face with her fingertips. Her husband had been the most powerful and the most beloved man in town, but Lela had mostly kept to herself. Few knew her well. The music, a far-off radio, changed from song to song, back to the announcer, back to song. When her glass was empty, Lela held it up to Clyde to refill, gesturing to an unlocked cabinet where he found the bourbon. Returning her refreshed glass, he sat next to her on the couch and she bent a tiny bit closer to him. He thought of Martha Harding, whom he had seen only at her viewing-she was hollow-looking, carefully embalmed. It was the first dead person young Clyde, then fifteen years old, had ever seen.

"It's too big. It's like driving a bus."

"Ma'am?"

She looked at him. "He must have left early," she said. "I was still asleep."

The elevator music continued, interrupted again by the announcer's lilting voice. Clyde did not argue with Lela, but instead let her sit there and come to understanding. She closed her eyes, and he began to move his hand up and down her back. At another time the gesture might have seemed too familiar. Now, though, in the moment of her stark grief, her drinking, the awful, shapeless music, this seemed the only thing for Clyde to do. He was a widower, ten years on his own now, and was unpracticed in the art of offering sympathy. His palm moved slowly against the small knots of vertebrae and Lela Harding seemed more fragile with each passing.

She touched her temples. "I wish we'd get some rain."

Clyde left after dark, the radio still playing, and unwilling to return home, looped the streets of town and the outlying county roads until dawn. He drove past his son's trailer, in the woods behind the school, past his neighbors' houses, past the factory. The downtown shops were silent and dark except for the soft buzzing of the streetlights and the perennial blue glow of the Pepsi fountain inside the Tuesday Diner.

* * *

The body was brought to Thompson's Funeral Home, and in the morning, Holland Thompson, the undertaker, set about preparing it for internment. Holland was a slow, methodical man who would have been a surgeon except he preferred a cleaner, more exact succession of tasks. He worked alone in a room furnished with only the table and his instruments, the cabinet, the industrial sink, and a portable radio tuned to a station that played covers of old pop songs. His married, childless daughter Celeste came, knocked shortly on the door, and then opened it without invitation. Her father, irritated at the interruption, turned sharply to her, and though Percy Harding was barely recognizable in his mangled state, she knew at once who it was laid out there on the cold steel table.

She gasped. Though the daughter of a mortician, she had never seen such a corpse. The body was so completely dead-simply emptied of life-and yet so untouched. His skin had not yet turned waxy and unreal, and he wasn't terribly bloody. Instead, the body was rumpled, a misshapen scattering of broken bones sealed over by skin and a blue jogging suit.

"It was a train," Holland said unnecessarily-Celeste had already heard what had happened, indeed had been the one to answer the phone. She had known Percy Harding, now dead, was coming to them. Her father shook his head over the particular violence of the tragedy, the degree of technical skill his job now required of him. He turned to his cabinet to select a thin, sharp needle and a spool of wire. He gestured to his daughter with a pair of surgical scissors.

"You keep this to yourself," he said.

"All right," she said, and hurried out.

She was still clutching her car keys when she whispered her discovery to the checkout girl at Lucky Grocery. "One hundred percent crushed," Celeste told her.

The checkout girl, a can of green beans in her hand, stopped, looking up at Celeste. The buyer of the green beans, a woman with two small children at her knees, asked, "What did you say?" though she'd heard Celeste well enough. She picked up the littler of her two boys and listened: Celeste, in a whisper, described what she had seen.

The news began swirling out, Celeste and the checkout girl and then the mother of the little boys and the bag boy all speaking of it there at the front of the store. Of course many had already heard that Percy Harding had died-it was in the local papers-but few had spoken to someone who had actually seen the body. Celeste repeated again and again, "One hundred percent crushed," and nodded at the blank faces, their brows wrinkled, their mouths half forming questions as the image settled in. Those coming in and those leaving heard and lingered; with time, a murmuring knot collected there. There were shoppers who had come off third shift a few hours earlier: the women still had their hair tied back. The men had their work boots on. Some were off work this morning, come in blue jeans and sweatshirts to pick up groceries for tonight's supper, and a few were in dressy slacks and sweater vests, late for their office jobs, dropping by to pick up coffee and pastries for their coworkers. They listened to Celeste describe what she had seen, and they began to understand: Percy Harding had been struck-destroyed-by a train.

The shock and sorrow of it clung to them as they stood by the automatic sliding glass doors, too numb to move. After a time, though, they remembered themselves and started to leave, some with thoughts of going to retrieve their children early from school, some to wait for the day-shift workers to come down the hill from the factory at four, and some to go home and sort it out, this horrible thing that had happened here, in their own small realm of church, friends, and work. Each recollected an actual encounter with the man, or at the very least, a sighting, and those remembered moments were absorbingly macabre now. The people recalled what they could of Percy Harding and looked, through time passed, for some foretelling, some hint, of the present disaster.

"He was a rock," one worker told another, and they both nodded. It was true-Percy Harding had been the town's single greatest support-but this was also the beginning of the kinds of legends people create after a passing.

"Harding will never be the same. We will never be the same," another said.

"It's true, it's true," came a response.

They referred to the incident as an accident, though many went home to confront their loved ones with the chilling uncertainty as to how a man might be struck by a train without either lying down for it or else standing resolutely on the tracks. People speculated. One man recalled a scene in a movie where a woman's shoe got wedged between the ground and the rail and the woman had struggled to free herself in time.

Clyde Winston stopped by the post office on his way home from the station late that afternoon. Hearing one of his neighbors speak of Percy's death, relaying a description, largely distorted, of the condition he was found in, he remembered the granite look of Lela Harding's eyes, how fragile the bones in her back had felt under his hand. From the post office, he went to his son's mobile home behind the junior high school rather than return to his own dark cave of a house. He leaned against the kitchen sink with a tepid glass of water and said, "It just don't make sense." He took a drink, shook his head, and said again, "It just don't."

"You're right there," his son agreed. "A man does not stand in the way of a train unless he means to get hit." He was still a moment, thinking, watching his father. "Or unless he's crazy," he added. He stood gripping the back of a kitchen chair, opening and closing his fingers to ease the tension in his knuckles. Ray Winston was a large man, his sturdy limbs and broad chest in proportion to his more than six feet of height. He wore his curly brown hair longish, just over the collar of his county-issued work shirt. In a softer tone, he continued, "And no one even guessing at it, not even knowing he was capable of it."

The two were quiet for a moment, considering the dead man's intentions. A chill breeze seeped through the slipshod hinges of the aluminum trailer even as sunshine beat through the uncurtained windows, lighting up dirt smudges here and there across the pane. Ray Winston was the groundskeeper for the county, mostly keeping up the yard of the junior high and high school, built on neighboring lots, and the grade schools across the way. He was also a part-time preacher, ordained by the power of the Spirit and none other, bringing the good news to the poor, the downtrodden. He kept his own worldly load light. He belonged to no church and did not do his preaching while lounging on a leather chesterfield in a great house on a hill, but instead stood on the doorsteps of Goliath, visiting the physically ill and the spiritually unwell. Now, also unlike Martha Harding, he kept his silence, waiting to see what else Clyde needed to say. He had learned that much-the ministry of listening-from his father.

Clyde had served the town of Goliath for decades. He had dealt with any number of domestic squabbles, drunken insanities, and break-ins. There had also been acts of vandalism, fits of meanness, and episodes of blatant stupidity. He had seen other suicides. But there was something different in this one. It was as if every person in town had put their own bodies in way of the train and were all broken now, spiritless.

After a moment, Clyde set his glass down and spoke.

"A person goes that far," he said, "he takes the rest of us partway with him." He stared squarely into his son's eyes. "You can't unsee a thing like that, you can't unlive it."

Vincent didn't answer. Outside, the clouds swept across the sky in quick-time, blossoming orange, then pink, then blue gray.

主題書展

更多

主題書展

更多書展今日66折

您曾經瀏覽過的商品

購物須知

外文書商品之書封,為出版社提供之樣本。實際出貨商品,以出版社所提供之現有版本為主。部份書籍,因出版社供應狀況特殊,匯率將依實際狀況做調整。

無庫存之商品,在您完成訂單程序之後,將以空運的方式為你下單調貨。為了縮短等待的時間,建議您將外文書與其他商品分開下單,以獲得最快的取貨速度,平均調貨時間為1~2個月。

為了保護您的權益,「三民網路書店」提供會員七日商品鑑賞期(收到商品為起始日)。

若要辦理退貨,請在商品鑑賞期內寄回,且商品必須是全新狀態與完整包裝(商品、附件、發票、隨貨贈品等)否則恕不接受退貨。