騎鵝歷險記(中英雙語典藏版)

商品資訊

系列名:愛藏本

ISBN13:9786263201392

替代書名:The Wonderful Adventures of Nils

出版社:晨星

作者:賽爾瑪.拉格洛芙-著; 鐘文君; Bertil Lybeck-繪圖

譯者:李毓昭

出版日:2022/06/13

裝訂/頁數:精裝/360頁

規格:21cm*14.8cm*3.1cm (高/寬/厚)

版次:2

商品簡介

作者簡介

目次

書摘/試閱

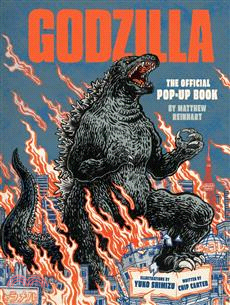

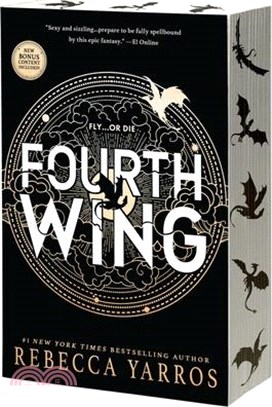

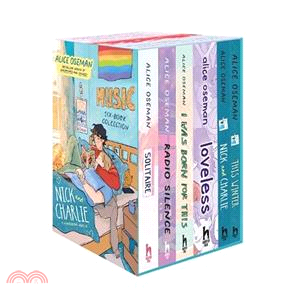

相關商品

商品簡介

★第一部獲得諾貝爾文學獎的兒童文學作品★

★瑞典國民童話★

當慣惡霸的孩子瞬間縮小!一場將改變一生的歷險

十四歲的尼爾斯性格頑劣,時常以虐待動物為樂。一天,他惹惱了家中的精靈,被施了魔法,變成身體只有拇指大小的小精靈。尼爾斯驚慌之餘發現自己聽得懂動物的語言,想像動物們打聽小精靈的下落,卻因為過去的劣行沒有任何動物願意幫助他。

當尼爾斯看見家中豢養的白公鵝莫爾登準備追隨野鵝飛往北方時,情急之下竟騎上了鵝背!他和莫爾登一路冒險犯難,原本在小動物間惡名昭彰的尼爾斯終於學會了善待動物、幫助他人,也漸漸愛上了在野外旅行的日子,然而當鵝群飛回南方,尼爾斯想變回人類要付出的代價卻是……

賽爾瑪.拉格洛芙以生動的想像及敏銳的洞察描繪瑞典的歷史與風土,藉由一段段深刻故事探討自然環境、動物、人類之間的關係,並展現其崇高的理想主義,即每一條生命都彌足珍貴,正直、善良是人類應追求的美好品德──使我們有勇氣面對因從善帶來的痛苦與困境,而不背棄自己的良心。

注目焦點

◎喜愛捉弄動物成性的尼爾斯,該怎麼與視他為壞傢伙的動物們和諧相處呢?

◎身軀變小的尼爾斯將會產生怎樣的心理轉變呢?

◎除了認識許多野生動物,跟著尼爾斯飛越歐洲,一同了解瑞典地理與傳奇

◎將尼爾斯變小的精靈開出了什麼樣的條件,才願意將尼爾斯重新變為人呢?

本書特色

※中英雙語版

※經典質感裝幀,具傳承典藏價值

※精修、簡易好讀

★瑞典國民童話★

當慣惡霸的孩子瞬間縮小!一場將改變一生的歷險

十四歲的尼爾斯性格頑劣,時常以虐待動物為樂。一天,他惹惱了家中的精靈,被施了魔法,變成身體只有拇指大小的小精靈。尼爾斯驚慌之餘發現自己聽得懂動物的語言,想像動物們打聽小精靈的下落,卻因為過去的劣行沒有任何動物願意幫助他。

當尼爾斯看見家中豢養的白公鵝莫爾登準備追隨野鵝飛往北方時,情急之下竟騎上了鵝背!他和莫爾登一路冒險犯難,原本在小動物間惡名昭彰的尼爾斯終於學會了善待動物、幫助他人,也漸漸愛上了在野外旅行的日子,然而當鵝群飛回南方,尼爾斯想變回人類要付出的代價卻是……

賽爾瑪.拉格洛芙以生動的想像及敏銳的洞察描繪瑞典的歷史與風土,藉由一段段深刻故事探討自然環境、動物、人類之間的關係,並展現其崇高的理想主義,即每一條生命都彌足珍貴,正直、善良是人類應追求的美好品德──使我們有勇氣面對因從善帶來的痛苦與困境,而不背棄自己的良心。

注目焦點

◎喜愛捉弄動物成性的尼爾斯,該怎麼與視他為壞傢伙的動物們和諧相處呢?

◎身軀變小的尼爾斯將會產生怎樣的心理轉變呢?

◎除了認識許多野生動物,跟著尼爾斯飛越歐洲,一同了解瑞典地理與傳奇

◎將尼爾斯變小的精靈開出了什麼樣的條件,才願意將尼爾斯重新變為人呢?

本書特色

※中英雙語版

※經典質感裝幀,具傳承典藏價值

※精修、簡易好讀

作者簡介

賽爾瑪.拉格洛芙 (Selma Lagerlöf,1858-1940)

出生於瑞典韋姆蘭省,從斯德哥爾摩羅威爾女子師範學院畢業後,開始一邊教書一邊寫作,1891年出版她的第一部作品《戈斯泰.貝林的故事》,這本以她家鄉做為背景的小說廣受好評,拉格洛芙成為暢銷作家。1895年她辭去教職,專心投入文學創作,期間也遊歷各國為其之後的多部作品尋找題材。50歲時受瑞典國家教師聯盟委託,為瑞典孩童編寫一部地理書。歷經4年,拉格洛芙走訪瑞典各地,最終藉由一個男孩被施法縮小成精靈、騎著公鵝遊歷瑞典的故事,生動豐富地描繪瑞典的自然地理、民間故事與傳奇,她也在1909年以這部《騎鵝歷險記》成為首位獲得諾貝爾文學獎的女性。

繪者簡介

鐘文君

專職網頁、插畫、視覺設計。從業多年,獨具特色的繪畫風格充滿童趣不失詼諧韻味與美感,熱中於產品開發。

Bertil Lybeck

瑞典藝術家/插畫家。插圖中完美結合當代藝術特徵與傳統技法。

譯者

李毓昭

曾任出版社編輯,從事翻譯工作十餘年,譯作類別廣泛,包括經典文學、成功勵志、商業管理、生活學習。譯有《撒種人》、《發現教堂的藝術》、《貓咪你想說什麼》、《一分鐘經理》、《50歲以後,不要吃碳水化合物》等。

出生於瑞典韋姆蘭省,從斯德哥爾摩羅威爾女子師範學院畢業後,開始一邊教書一邊寫作,1891年出版她的第一部作品《戈斯泰.貝林的故事》,這本以她家鄉做為背景的小說廣受好評,拉格洛芙成為暢銷作家。1895年她辭去教職,專心投入文學創作,期間也遊歷各國為其之後的多部作品尋找題材。50歲時受瑞典國家教師聯盟委託,為瑞典孩童編寫一部地理書。歷經4年,拉格洛芙走訪瑞典各地,最終藉由一個男孩被施法縮小成精靈、騎著公鵝遊歷瑞典的故事,生動豐富地描繪瑞典的自然地理、民間故事與傳奇,她也在1909年以這部《騎鵝歷險記》成為首位獲得諾貝爾文學獎的女性。

繪者簡介

鐘文君

專職網頁、插畫、視覺設計。從業多年,獨具特色的繪畫風格充滿童趣不失詼諧韻味與美感,熱中於產品開發。

Bertil Lybeck

瑞典藝術家/插畫家。插圖中完美結合當代藝術特徵與傳統技法。

譯者

李毓昭

曾任出版社編輯,從事翻譯工作十餘年,譯作類別廣泛,包括經典文學、成功勵志、商業管理、生活學習。譯有《撒種人》、《發現教堂的藝術》、《貓咪你想說什麼》、《一分鐘經理》、《50歲以後,不要吃碳水化合物》等。

目次

第一章 男孩

第二章 凱布訥山的阿卡

第三章 尼爾斯美妙的旅程

第四章 格里敏城堡

第五章 克拉山的大鶴舞

第六章 雨天

第七章 羅耐畢河畔

第八章 卡爾斯克羅納

第九章 厄蘭南角

第十章 小卡爾斯島

第十一章 斯莫蘭的傳說

第十二章 烏鴉

第十三章 老農婦

第十四章 從塔山到大鳥湖

第十五章 粗麻布與融冰

第十六章 水災

第十七章 歐莎和小麥茲

第十八章 與拉普人共處

第十九章 啟程回家

第二十章 海爾葉達倫的傳說

第二十一章 海島寶藏

第二十二章 飛向威門荷格

第二十三章 回家

第二十四章 告別野鵝

01 The Boy

02 Akka from Kebnekaise

03 The Wonderful Journey of Nils

04 Glimminge Castle

05 The Great Crane Dance on Kullaberg

06 In Rainy Weather

07 By Ronneby River

08 Karlskrona

09 Öland's Southern Point

10 Little Karl's Island

11 The Legend of Småland

12 The Crows

13 The Old Peasant Woman

14 From Taberg to the Big Bird Lake

15 The Homespun Cloth and the Breaking Up of the Ice

16 The Flood

17 Osa, the Goose Girl, and Little Mats

18 With the Laplanders

19 Homeward Bound

20 Legends from Härjedalen

21 The Treasure on the Island

22 The Journey to Vemminghög

23 Home at Last

24 The Parting with the Wild Geese

第二章 凱布訥山的阿卡

第三章 尼爾斯美妙的旅程

第四章 格里敏城堡

第五章 克拉山的大鶴舞

第六章 雨天

第七章 羅耐畢河畔

第八章 卡爾斯克羅納

第九章 厄蘭南角

第十章 小卡爾斯島

第十一章 斯莫蘭的傳說

第十二章 烏鴉

第十三章 老農婦

第十四章 從塔山到大鳥湖

第十五章 粗麻布與融冰

第十六章 水災

第十七章 歐莎和小麥茲

第十八章 與拉普人共處

第十九章 啟程回家

第二十章 海爾葉達倫的傳說

第二十一章 海島寶藏

第二十二章 飛向威門荷格

第二十三章 回家

第二十四章 告別野鵝

01 The Boy

02 Akka from Kebnekaise

03 The Wonderful Journey of Nils

04 Glimminge Castle

05 The Great Crane Dance on Kullaberg

06 In Rainy Weather

07 By Ronneby River

08 Karlskrona

09 Öland's Southern Point

10 Little Karl's Island

11 The Legend of Småland

12 The Crows

13 The Old Peasant Woman

14 From Taberg to the Big Bird Lake

15 The Homespun Cloth and the Breaking Up of the Ice

16 The Flood

17 Osa, the Goose Girl, and Little Mats

18 With the Laplanders

19 Homeward Bound

20 Legends from Härjedalen

21 The Treasure on the Island

22 The Journey to Vemminghög

23 Home at Last

24 The Parting with the Wild Geese

書摘/試閱

第1章 男孩

精靈 三月二十日,星期日

從前,有個身材高瘦、動作敏捷的十四歲男孩,他沒什麼本事,成天喜歡做的事就是吃和睡,除此之外最愛調皮搗蛋。

星期日早晨,男孩的父母親正準備去教堂。男孩穿著襯衫,坐在桌邊,心想這下可好,爸媽都要出門,他有好幾個小時可以自由玩樂。「真棒!我可以把爸爸的槍拿下來把玩射擊,沒人管我。」

可是父親似乎猜中了男孩的心思,人都走到門口了,卻又停下來,轉身對他說:「你不和我們去教堂,至少要在家裡唸唸講道集。你願意嗎?」「願意,我一定會唸的。」男孩雖然嘴巴這麼說,心裡卻想著,如果他不想唸,當然就不會唸了。

男孩媽媽迅速地從壁爐邊的書架取下《路德講道集》,放在窗前的桌上,翻開當天要讀的那一篇。她還翻開《新約聖經》,放在講道集旁邊,最後把大扶手椅拖拉到桌前。

父親走到男孩身旁,嚴厲地說:「好好唸!我們回來時,我會一頁一頁地考你,要是你漏掉一頁沒唸,就有苦頭吃了。」

「這篇講道總共有十四頁半,」母親叮嚀。「你要馬上坐下來唸,不然會唸不完。」

他們說完就出門了。男孩在門口目送他們時,感覺好像中計了。「他們一定正在慶幸想了個好辦法,讓我在他們上教堂禮拜時不得不坐下來看書。」

可是他的父母親並沒有在慶幸什麼,反而相當苦惱。父親抱怨著兒子又笨又懶,上了學校也無心唸書,一點用處也沒有,連叫他看鵝都不放心。母親不否認這些批評,可是她最擔心的是兒子的頑劣。他會虐待動物,對人也不懷好意。母親說:「但願上帝讓他冷酷的心變得溫和!不然他會給他自己和我們招來不幸。」

男孩站了許久,考慮要不要去唸講道集。他終於得到結論:這次最好聽話。他坐進扶手椅,開始讀書。可是他低聲唸了一會兒,那咕咕噥噥的聲音似乎有催眠作用,讓他打起瞌睡。

外頭的天氣十分晴朗,木門半掩,在屋裡聽得見雲雀的啼唱。母雞和鵝群在院子裡漫步,牛隻也感覺到春天的氣息,不時哞哞叫著,表示嘉許。

男孩一邊讀書一邊打盹,與睡意搏鬥。「不行!我不可以睡。」他心想:「不然整個早上我都唸不完。」可他還是睡著了。

他不知道自己睡了多久,有一道輕微的響聲把他吵醒。

窗臺上的小鏡子正對著男孩,幾乎能從裡面看到整個屋內。男孩抬起頭來,正好看到鏡子,瞥見母親的衣箱蓋開著。

他的母親有一個束著鐵條的橡木箱,向來不准別人碰。裡面收藏著祖母留給她的物品,她非常愛惜那些東西。其中有幾件過時的農婦裝、漿好的白麻頭巾,以及沉甸甸的銀飾品。他母親也曾想要丟棄這些舊東西,卻又捨不得。

這時,男孩從鏡中清楚地看到箱蓋掀開著。他不明白怎麼會打開,因為他單獨在家時,母親絕不會讓那只珍貴的箱子開著。

他擔心是小偷溜進屋裡,他不敢動,只是靜靜坐著盯著鏡子。

他等著小偷現身時,看到箱子的邊緣有黑影。他一看再看,不敢相信自己的眼睛。那個起初像影子的東西變得越來越清晰,很快就看出那是個真的,是活生生的精靈―跨坐在箱子的邊緣上!

男孩確實聽說過精靈的故事,但是從沒想到他們竟然這麼小巧,坐在箱子邊的那個精靈不會比一隻手掌高。精靈有一張年老的臉,布滿皺紋,但沒有鬍鬚,身穿黑長袍、齊膝褲,戴著寬邊黑帽,他的衣著整齊美觀。他從箱子拿出一塊繡花布,坐在那裡端詳著上頭的舊式手工,沒有注意到男孩醒了。

男孩雖然感到驚訝,但一點也不害怕,那麼小的東西有什麼好怕的。何況精靈的神情專注,完全沒有察覺到四周的動靜。男孩心想,戲弄他應該很好玩,例如把他推進箱子,再闔上蓋子。

他一看見捕蝶網就伸手去拿,然後跳起來朝箱子邊緣揮過去。男孩根本不知道自己是怎麼辦到的,可是真的網住精靈了。可憐的小傢伙栽倒在網子深處,沒辦法掙脫。

起初男孩只是小心地搖晃網子,讓精靈無法站穩,也無法攀爬上來。

精靈可憐兮兮地求饒男孩釋放他。他說多年來一直在賜給男孩一家好運,男孩應該善待他。如果男孩肯放他走,他願意給他一枚舊硬幣、一把銀湯匙和一個像他父親的銀錶一樣大的金幣。

男孩覺得精靈承諾的東西不算多,可是捉到精靈之後,他開始害怕了,覺得自己正跟不屬於這個世界的怪異東西打交道,他很樂意擺脫精靈,馬上答應這筆交易。他停止搖晃網子,讓精靈爬出來。可是當精靈幾乎要爬出網子時,男孩又想到應該要求更多財富和好東西,至少應該要求精靈把講道集的內容塞進他的腦子裡。「我真笨,怎麼能讓他跑掉!」這麼想著,他開始粗魯地搖晃網子,所以精靈又跌了下來。

瞬間,男孩挨了個結實的巴掌,覺得整顆頭都要碎掉了。他被甩出去,從一面牆撞到另一面牆,最後倒地不起,失去意識。

醒來時,屋裡只有他一個人。箱蓋是闔上的,捕蝶網好端端地掛在窗邊。要不是頭和臉頰因為挨了耳光而感到熱辣,他會相信是一場夢。「無論如何,爸媽都會認為我是在做夢。」他心想:「他們絕不會因為精靈而饒過我沒唸講道集,我最好趕快開始唸。」

可是當他起身要走到桌邊時,發覺事情不太對勁。屋子不可能變大,但為什麼桌子變得比平常還要遠呢?那把椅子又是怎麼一回事?它看起來不會比之前大,可是他卻得踩著底下的橫桿,才能爬上座位。桌子也是一樣,他必須爬上椅子扶手,才看得到桌面。

「發生什麼事了?」男孩說。「一定是精靈對桌子和椅子,還有整個屋子都施了魔法。」

講道集仍放在桌上,看似無異,可是一定有哪裡有問題,因為他如果不站在書上,就一個字也看不到。

他唸了幾行字後不經意地抬起頭,視線落到鏡子,馬上大叫:「哎!那還有一個!」鏡中有個戴著帽兜,穿著皮褲的小傢伙。

「啊,他的穿著和我一模一樣。」男孩說,他吃驚得拍著雙手。這時他看到鏡子裡的人也做出同樣的動作。他拉拉頭髮,捏捏手臂,扭動身體,鏡子裡的人都馬上照做。

男孩繞著鏡子跑了幾圈,看看有沒有小人藏在後面,可是什麼也沒發現。他開始嚇得全身發抖,現在他明白了,那個精靈對他施了魔法,鏡子裡的影像就是他自己。

野鵝

男孩無法相信自己變成精靈了。他想著:「這一定是一場夢,等一下我就會變回人類了。」

他站在鏡子前,閉上眼睛,希望幾分鐘後睜開眼睛時,一切都已過去。但事與願違,他的個子還是那麼小。就某方面來說,他和之前沒有兩樣。淡黃色的頭髮、遍布鼻子的雀斑、皮褲和襪子上的補丁都和之前相同,唯一的差別是全部都縮小了。

他可以確定,站在這裡等再久也沒用,必須想想辦法,而他想到的最聰明的辦法是去找那個精靈,和他講和。

男孩一邊哭一邊祈禱,答應做到所有他想得到的事。再也不說話不算話、惡作劇,或是在聽講道時睡著。只要他能夠變回人類,他願意成為樂於助人的乖孩子。可是無論他怎麼許願,都沒有用。

突然之間,他記起來曾經聽母親說過,精靈都住在牛棚裡,就決定去那邊看看。幸好屋子的門半開著,不然他根本搆不到門拴。他輕易地從門口溜出去。

他來到門廊,尋找他的木鞋,因為他在屋裡只穿著襪子,正想著要如何穿上那雙笨重的大鞋時,看到門階上有一雙小鞋。精靈竟然設想周到,對木鞋也施了魔法。這下子他更不安了,因為精靈顯然要折磨他很久。

有隻灰色的麻雀在屋子前面的木頭地板上跳躍。他一看到男孩就大叫:「啾啾!啾啾!看這個呆頭男孩尼爾斯!看這個拇指大的尼爾斯‧霍爾加松!」

院子裡的鵝和雞都轉過頭來看,然後發出嚇人的咯咯聲。公雞喊道:「活該!咕咕咕!他扯過我的雞冠!」母雞也一起叫著:「活該!」鵝聚在一起,抬頭問道:「是誰讓他變成這樣的?」

奇怪的是,男孩聽得懂他們的話。他吃驚地站在門階上聽,同時自言自語:「一定是因為我變成精靈了,所以聽得懂鳥語。」

他受不了母雞一直說他活該,就朝他們扔出一顆石頭,大吼:「閉嘴,你們這群畜生!」

可是母雞不再怕他了,整群母雞衝過去,圍著他,出聲叫罵:「你活該!你活該!」

男孩想要逃跑,雞群卻在後面追著,直到他覺得耳朵快要聾了。要是他們家的貓沒有走過來,也許他永遠也擺脫不了。雞群一看到貓就安靜下來,假裝只是在啄地上的蚯蚓。

男孩迅速跑到貓那裡說:「親愛的貓咪!你一定知道這一帶所有躲藏的地方吧?乖小貓,告訴我哪裡可以找到精靈?」

貓咪沒有立即回答。他悠閒地坐下來,尾巴優雅地在腳掌上圍成圈,兩眼瞪著男孩。那是隻大黑貓,胸前有一塊白斑,毛皮光滑、柔軟,在日光下顯出光澤。他的爪子內縮,暗灰色的瞳孔瞇成細縫,看起來很溫馴。

「我知道精靈在哪裡,」貓咪柔聲說,「但我不會告訴你。」

「親愛的貓咪,你一定要告訴我!」男孩哀求。「你看不出他對我施了魔法嗎?」

貓的眼睛微睜,透出一道寒光。他轉了一圈,發出滿足的呼嚕聲,然後回答:「就因為你經常拉我的尾巴,所以我要幫你嗎?」

男孩生起氣來,忘記自己已經變小了。「哦!那我要再去拉你的尾巴。」他說著,跑向那隻貓。

那隻貓一轉眼豎起每一根毛髮,拱著背,伸長四肢,爪子在地上刮搔,尾巴變得又粗又短,耳朵往後縮,口吐唾沫,睜大的眼睛閃現火花似的光芒。

男孩不想對貓示弱,就又向前一步。貓跳起來撲向男孩,把男孩推倒,前腳按著他的胸部,張大的嘴巴對著他的喉嚨。

男孩感覺到銳利的爪子穿透他的衣服,刺進皮膚,犬齒碰到他的喉嚨。他盡可能大喊救命,卻沒有人過來。以為自己一定沒命了,卻發覺貓縮回爪子,把他放開。

「看在女主人的份上,放你一馬。我只是讓你知道,現在我們兩個之間誰比較佔上風。」貓說完就走開了,變回和之前一樣溫和。男孩羞愧得說不出話來,只好趕緊去牛棚找精靈。

那裡有三頭牛,年紀都很大了。可是男孩一進來,就引起一陣怒吼和騷動,足以讓人以為裡面至少養了三十頭牛。

「哞,哞,哞,」三頭牛一起叫喊。男孩聽不清楚他們說什麼,因為一隻比一隻吼得更大聲。

男孩想問精靈的事,可是聲音進不去他們的耳裡。就像之前他把陌生的狗放進去時一樣,他們猛踢後腿,搖晃側腹,頭伸直,牛角對準了男孩。

「過來!」五月玫瑰說。「我要踢你一腳,讓你難以忘記!」

「過來,」金百合說。「我要你在我的角上跳舞!」

「過來,去年夏天你用木鞋扔我,我要讓你嚐嚐那是什麼滋味!」星星說。

五月玫瑰是年紀最大、最聰明,也是最生氣的。「你過來,我要讓你吃點苦頭,因為你曾經多次害你媽媽打翻牛奶桶,也因為你,她常常站在這裡為你掉眼淚。」

男孩很想跟他們說,他很後悔做了那些壞事,以後一定會乖乖的,只要告訴他精靈在哪裡。可是那三頭牛不肯聽他說話,不斷叫罵,男孩害怕他們會掙脫繩子,覺得現在最好安靜地離開牛棚。

男孩沮喪地走出來,他知道這裡不會有人願意幫他找到精靈。他爬到農場圍牆上,想著如果不能變回人類會怎樣。爸媽從教堂回來時一定會很吃驚。消息會傳到全國,人們會從四面八方跑來看他。也許爸媽會帶他到城市的市場供人觀賞。候鳥乘風飛行,穿越波羅的海飛向北方。野鵝排成人字形飛著。

野鵝看到在農場漫步的家鵝時,就會飛近地面大叫:「一起來吧!一起飛向高山!」家鵝都不禁抬頭傾聽,可是都理智地回答:「我們在這裡過得很好。」

這天的天氣特別晴朗怡人,隨著一群群野鵝飛過,家鵝變得越來越興奮。有時他們會拍動翅膀,但總是有一隻母鵝跟他們說:「別傻了,跟著那些傢伙會挨餓受凍的!」

有隻年輕的鵝名叫莫爾登,對旅行產生憧憬。他說:「要是再有一群飛過來,我就要跟他們走。」

真的又來了一群野鵝,和之前的鵝群一樣大聲叫喊,年輕的公鵝莫爾登回答:「等一等,等一等,我來了。」

他張開翅膀,升到空中,可是他不習慣飛行,很快就掉下來。

儘管如此,野鵝們聽見了公鵝莫爾登的叫聲,就折回來慢慢飛,看他有沒有跟來。

「等一等!」莫爾登再度嘗試飛起來。男孩坐在圍牆上,每句話都聽見了。他心想:「如果這隻大公鵝飛走了,對爸媽來說是很大的損失。」光想到這一點,他便忘了自己有多弱小,跳起來用雙臂抱住公鵝的脖子。「不行,你這次先別走。」他大叫。

公鵝正想著如何騰空飛起,來不及甩掉男孩,就帶著他飛到空中了。

他們一下子就飛到高空,男孩倒抽一口氣,才剛覺得可以把手放開時,已經離地面很高,掉到地上一定會沒命。

唯一能做的就是讓自己舒服一點,所以他騎到公鵝的背上,把手插進羽毛中抓緊,才不會摔下來。

大方格布

男孩覺得頭暈眼花,過了很久才恢復神智。風呼嘯而過,羽毛的沙沙聲和拍動翅膀的聲音聽起來彷彿暴風。十三隻鵝飛在他旁邊,一邊振翅一邊呱呱叫著。

過了一會兒他才清醒過來,覺得應該問問鵝群要帶他去哪裡。可是並不容易,因為他不敢往下看,他確信自己一看就會頭暈。

野鵝飛得並不高,因為新夥伴無法在稀薄的空氣中呼吸。也因為這樣,他們飛得比平常緩慢。

男孩朝底下瞥了一眼,感覺好像鋪著一大塊布,由許多大小不同的格子拼湊而成。「我到底是在哪裡?」他很想知道。

他只看到一塊塊格子。有的是菱形,有的是長方形,沒有一個是圓的或彎的。「下面這塊大方格布到底是什麼呢?」他自言自語,並不指望聽到回答。

可是圍在他旁邊的野鵝隨即喊道:「田地和草地。」

他這才認出鮮綠色的格子是裸麥田,灰黃色的格子是去年夏天收割完的田地,褐色的是老苜蓿地,黑色的是廢棄的放牧地或犁過的休耕地。

男孩看到一切都變成格子時,不禁哈哈大笑。可是野鵝聽到他的笑聲,就以斥責的口氣大喊:「肥美的土地!」

男孩正經起來,心想:「你居然還笑得出來,想想是誰遇到了一個人類所能遇到最悲慘的事!」他嚴肅了一會兒,但不久又笑了出來。他習慣了騎鵝和飛行速度,可以一邊抓著鵝背一邊想事情。

他們經過一些裝著高大煙囪的笨拙建築,四周有許多小房子。「這裡是糖廠。」公雞群嚷著。男孩在鵝背上吃了一驚。他認得這裡,因為離他家不遠。

去年曾來這裡打工,不過從上面看起來,全部都變了樣。

當時他認識了看鵝女孩歐莎和小麥茲,很想知道他們是否還在這裡。要是他們知道他正在飛過他們的頭頂,不知道會怎麼說!

野鵝從家鵝頭上飛過去時是最快樂的!他們會飛得很慢,同時往下叫喊:「我們要飛到山上。你們要一起來嗎?」但家鵝回答:「這國家還是冬天,你們太早出國了。飛回來!飛回來!」

野鵝們飛得更低了,好讓底下的鵝聽得更清楚。「一起來!我們會教你們飛行和游泳。」家鵝生氣了,不肯再回答。

野鵝們飛得越來越低,幾乎要碰到地面,然後快如閃電地升空,彷彿受到驚嚇。「哎唷,哎唷!」他們大叫。「這些傢伙不是鵝,他們只是羊,只是羊。」地上的鵝聽了都氣壞了,紛紛叫罵。

男孩聽見這番嘲諷時笑了,但想起身上的惡運,又哭了起來。但過沒多久又笑了。

01 THE BOY

THE ELF Sunday, March twentieth.

Once there was a boy. He was―let us say―something like fourteen years old; long and loose-jointed. He wasn't good for much. His chief delight was to eat and sleep; and after that―he liked best to make mischief.

It was a Sunday morning and the boy's parents were getting ready to go to church. The boy sat on the edge of the table, in his shirt sleeves, and thought how lucky it was that both father and mother were going away, and the coast would be clear for a couple of hours. “Good! Now I can take down pop's gun and fire off a shot, without anybody's meddling interference,” he said to himself.

But it was almost as if father should have guessed the boy's thoughts, for just as he was on the threshold―ready to start―he stopped short, and turned toward the boy. “Since you won't come to church with mother and me,” he said, “the least you can do, is to read the service at home. Will you promise to do so?” “Yes,” said the boy, “that I can do easy enough.” And he thought, of course, that he wouldn't read any more than he felt like reading.

In a second his mother was over by the shelf near the fireplace, and took down Luther's Commentary and laid it on the table, in front of the window―opened at the service for the day. She also opened the New Testament, and placed it beside the Commentary. Finally, she drew up the big arm-chair.

His father walked up to the boy, and said in a severe tone: “Remember, that you are to read carefully! For when we come back, I shall question you thoroughly; and if you have skipped a single page, it will not go well with you.”

“The service is fourteen and a half pages long,” said his mother. “You'll have to sit down and begin the reading at once, if you expect to get through with it.”

With that they departed. And as the boy stood in the doorway watching them, he thought that he had been caught in a trap. “There they go congratulating themselves, I suppose, in the belief that they've hit upon something so good that I'll be forced to sit and hang over the sermon the whole time that they are away,” thought he.

But his father and mother were certainly not congratulating themselves upon anything of the sort; but, on the contrary, they were very much distressed. Father complained that he was dull and lazy; he had not cared to learn anything at school, and he was such an all-round good-for-nothing, that he could barely be made to tend geese. Mother did not deny that; but she was most distressed because he was wild and bad; cruel to animals, and ill-willed toward human beings. “May God soften his hard heart, and give him a better disposition!” said the mother, “or else he will be a misfortune, both to himself and to us.”

The boy stood for a long time and pondered whether he should read the service or not. Finally, he came to the conclusion that, this time, it was best to be obedient. He seated himself in the easy chair, and began to read. But when he had been rattling away in an undertone for a little while, this mumbling seemed to have a soothing effect upon him―and he began to nod.

It was the most beautiful weather outside! The cottage door stood ajar, and the lark's trill could be heard in the room. The hens and geese pattered about in the yard, and the cows, who felt the spring air away in their stalls, lowed their approval every now and then.

The boy read and nodded and fought against drowsiness. “No! I don't want to fall asleep,” thought he, “for then I'll not get through with this thing the whole forenoon.” But―somehow―he fell asleep.

He did not know whether he had slept a short while, or a long while; but he was awakened by hearing a slight noise back of him.

On the window-sill, facing the boy, stood a small looking-glass; and almost the entire cottage could be seen in this. As the boy raised his head, he happened to look in the glass; and then he saw that the cover to his mother's chest had been opened.

His mother owned a great, heavy, iron-bound oak chest, which she permitted no one but herself to open. Here she treasured all the things she had inherited from her mother, and of these she was especially careful. Here lay a couple of old-time peasant dresses, and starched white-linen head-dresses, and heavy silver ornaments and chains. Several times his mother had thought of getting rid of the old things; but somehow, she hadn't had the heart to do it.

Now the boy saw distinctly―in the glass―that the chest-lid was open. He could not understand how this had happened. She never would have left that precious chest open when he was at home, alone.

He was afraid that a thief had sneaked his way into the cottage. He didn't dare to move; but sat still and stared into the looking-glass.

While he waited for the thief to make his appearance, he began to wonder what that dark shadow was which fell across the edge of the chest. He looked and looked―and did not want to believe his eyes. But the thing, which at first seemed shadowy, became more and more clear to him; and soon he saw that it was something real. It was no less a thing than an elf who sat there―astride the edge of the chest!

To be sure, the boy had heard stories about elves, but he had never dreamed that they were such tiny creatures. He was no taller than a hand's breadth―this one, who sat on the edge of the chest. He had an old, wrinkled and beardless face, and was dressed in a black frock coat, knee-breeches and a broad-brimmed black hat. He was very trim and smart. He had taken from the chest an embroidered piece, and sat and looked at the old-fashioned handiwork with such an air of veneration, that he did not observe the boy had awakened.

The boy was surprised to see the elf, but he was not particularly frightened. It was impossible to be afraid of one who was so little. And since the elf was so absorbed in his own thoughts that he neither saw nor heard, the boy thought that it would be great fun to play a trick on him; to push him over into the chest and shut the lid on him, or something of that kind.

He had hardly set eyes on that butterfly-snare, before he reached over and snatched it and jumped up and swung it alongside the edge of the chest. He hardly knew how he had managed it―but he had actually snared the elf. The poor little chap lay, head downward, in the bottom of the long snare, and could not free himself.

The first moment the boy was only particular to swing the snare backward and forward; to prevent the elf from getting a foothold and clambering up.

The elf began to begged, oh! so pitifully, for his freedom. He had brought them good luck―these many years―he said, and deserved better treatment. Now, if the boy would set him free, he would give him an old coin, a silver spoon, and a gold penny, as big as the case on his father's silver watch.

The boy didn't think that this was much of an offer; but it so happened―that after he had gotten the elf in his power, he was afraid of him. He felt that he had entered into an agreement with something weird and uncanny; something which did not belong to his world, and he was only too glad to get rid of the horrid thing. For this reason he agreed at once to the bargain, and held the snare still, so the elf could crawl out of it. But when the elf was almost out of the snare, the boy happened to think that he ought to have bargained for large estates, and all sorts of good things. He should at least have made this stipulation: that the elf must conjure the sermon into his head. “What a fool I was to let him go!” thought he, and began to shake the snare violently, so the elf would tumble down again.

But the instant the boy did this, he received such a stinging box on the ear, that he thought his head would fly in pieces. He was dashed―first against one wall, then against the other; he sank to the floor, and lay there―senseless.

When he awoke, he was alone in the cottage. The chest-lid was down, and the butterfly-snare hung in its usual place by the window. If he had not felt how the right cheek burned, from that box on the ear, he would have been tempted to believe the whole thing had been a dream. “At any rate, father and mother will be sure to insist that it was nothing else,” thought he. “They are not likely to make any allowances for that old sermon, on account of the elf. It's best for me to get at that reading again,” thought he.

But as he walked toward the table, he noticed something remarkable. It couldn't be possible that the cottage had grown. But why was he obliged to take so many more steps than usual to get to the table? And what was the matter with the chair? It looked no bigger than it did a while ago; but now he had to step on the rung first, and then clamber up in order to reach the seat. It was the same thing with the table. He could not look over the top without climbing to the arm of the chair.

“What in all the world is this?” said the boy. “I believe the elf has bewitched both the armchair and the table―and the whole cottage.”

The Commentary lay on the table and, to all appearances, it was not changed; but there must have been something queer about that too, for he could not manage to read a single word of it, without actually standing right in the book itself.

He read a couple of lines, and then he chanced to look up. With that, his glance fell on the looking-glass; and then he cried aloud: “Look! There's another one!” For in the glass he saw plainly a little, little creature who was dressed in a hood and leather breeches.

“Why, that one is dressed exactly like me!” said the boy, and clasped his hands in astonishment. But then he saw that the thing in the mirror did the same thing. Then he began to pull his hair and pinch his arms and swing round; and instantly he did the same thing after him; he, who was seen in the mirror.

The boy ran around the glass several times, to see if there wasn't a little man hidden behind it, but he found no one there; and then he began to shake with terror. For now he understood that the elf had bewitched him, and that the creature whose image he saw in the glass―was he, himself.

THE WILD GEESE

The boy simply could not make himself believe that he had been transformed into an elf. “It can't be anything but a dream. If I wait a few moments, I'll surely be turned back into a human being again.”

He placed himself before the glass and closed his eyes. He opened them again after a couple of minutes, and then expected to find that it had all passed over―but it hadn't. He was―and remained―just as little. In other respects, he was the same as before. The thin, straw-coloured hair; the freckles across his nose; the patches on his leather breeches and the darns on his stockings, were all like themselves, with this exception―that they had become diminished.

No, it would do no good for him to stand still and wait, of this he was certain. He must try something else. And he thought the wisest thing that he could do was to try and find the elf, and make his peace with him.

He cried and prayed and promised everything he could think of. Nevermore would he break his word to anyone; never again would he be naughty; and never, never would he fall asleep again over the sermon. If he might only be a human being once more, he would be such a good and helpful and obedient boy. But no matter how much he promised―it did not help him the least little bit.

Suddenly he remembered that he had heard his mother say, all the tiny folk made their home in the cowsheds; and, at once, he concluded to go there, and see if he couldn't find the elf. It was a lucky thing that the cottage-door stood partly open, for he never could have reached the bolt and opened it; but now he slipped through without any difficulty.

When he came out in the hallway, he looked around for his wooden shoes; for in the house, to be sure, he had gone about in his stocking-feet. He wondered how he should manage with these big, clumsy wooden shoes; but just then, he saw a pair of tiny shoes on the doorstep. When he observed that the elf had been so thoughtful that he had also bewitched the wooden shoes, he was even more troubled. It was evidently his intention that this affliction should last a long time.

On the wooden board-walk in front of the cottage, hopped a gray sparrow. He had hardly set eyes on the boy before he called out: “Teetee! Teetee! Look at Nils goosey-boy! Look at Thumbietot! Look at Nils Holgersson Thumbietot!”

Instantly, both the geese and the chickens turned and stared at the boy; and then they set up a fearful cackling. “Good enough for him! Cock-el-i-coo, he has pulled my comb.” crowed the rooster. “Serves him right!” cried the hens. The geese got together in a tight group, stuck their heads together and asked: “Who can have done this?”

But the strangest thing of all was, that the boy understood what they said. He was so astonished, that he stood there as if rooted to the doorstep, and listened. “It must be because I am changed into an elf,” said he. “This is probably why I understand bird-talk.”

He thought it was unbearable that the hens would not stop saying that it served him right. He threw a stone at them and shouted:

“Shut up, you pack!”

However, he was no longer the sort of boy the hens need fear. The whole henyard made a rush for him, and formed a ring around him; then they all cried at once: “Served you right! Ka, ka, kada, served you right!”

The boy tried to get away, but the chickens ran after him and screamed, until he thought he'd lose his hearing. It is more than likely that he never could have gotten away from them, if the house cat hadn't come along just then. As soon as the chickens saw the cat, they quieted down and pretended to be thinking of nothing else than just to scratch in the earth for worms.

Immediately the boy ran up to the cat. “You dear pussy!” said he, “you must know all the corners and hiding places about here? You'll be a good little kitty and tell me where I can find the elf.”

The cat did not reply at once. He seated himself, curled his tail into a graceful ring around his paws―and stared at the boy. It was a large black cat with one white spot on his chest. His fur lay sleek and soft, and shone in the sunlight. The claws were drawn in, and the eyes were a dull gray, with just a little narrow dark streak down the centre. The cat looked thoroughly good-natured and inoffensive.

“I know well enough where the elf lives,” he said in a soft voice, “but I'm not going to tell you that.”

“Dear pussy, you must tell me where the elf lives!” said the boy. “Can't you see how he has bewitched me?”

The cat opened his eyes a little, so that the green wickedness began to shine forth. He spun round and purred with satisfaction before he replied. “Shall I perhaps help you because you have so often grabbed me by the tail?” he said at last.

Then the boy was furious and forgot entirely how little and helpless he was now. “Oh! I can pull your tail again, I can,” said he, and ran toward the cat.

The next instant the hair on the cat's body stood on end. The back was bent; the legs had become elongated; the claws scraped the ground; the tail had grown thick and short; the ears were laid back; the mouth was frothy; and the eyes were wide open and glistened like sparks of red fire.

The boy didn't want to let himself be scared by a cat, and he took a step forward. Then the cat made one spring and landed right on the boy; knocked him down and stood over him―his forepaws on his chest, and his jaws wide apart―over his throat.

The boy felt how the sharp claws sank through his vest and shirt and into his skin; and how the sharp eye-teeth tickled his throat. He shrieked for help, as loudly as he could, but no one came. He thought surely that his last hour had come. Then he felt that the cat drew in his claws and let go the hold on his throat.

“I'll let you go this time, for my mistress's sake. I only wanted you to know which one of us two has the power now.” With that the cat walked away―looking as smooth and pious as he did when he first appeared on the scene. The boy was so crestfallen that he didn't say a word, but only hurried to the cowhouse to look for the elf.

There were not more than three cows, all told. But when the boy came in, there was such a bellowing and such a kick-up, that one might easily have believed that there were at least thirty.

“Moo, moo, moo,” sang the three of them in unison. He couldn't hear what they said, for each one tried to out-bellow the others.

The boy wanted to ask after the elf, but he couldn't make himself heard because the cows were in full uproar. They carried on as they used to do when he let a strange dog in on them. They kicked with their hind legs, shook their necks, stretched their heads, and measured the distance with their horns.

“Come here!” said Mayrose, “and you'll get a kick that you won't forget in a hurry!”

“Come here,” said Gold Lily, “and you shall dance on my horns!”

“Come here, and you shall taste how it felt when you threw your wooden shoes at me, as you did last summer!” bawled Star.

Mayrose was the oldest and the wisest of them, and she was the very maddest. “Come here!” said she, “that I may pay you back for the many times that you have jerked the milk pail away from your mother; and for all the tears when she has stood here and wept over you!”

The boy wanted to tell them how he regretted that he had been unkind to them; and that never, never―from now on―should he be anything but good, if they would only tell him where the elf was. But the cows didn't listen to him. They made such a racket that he began to fear one of them would succeed in breaking loose; and he thought that the best thing for him to do was to go quietly away from the cowhouse.

When he came out, he was thoroughly disheartened. He could understand that no one on the place wanted to help him find the elf. He crawled up on the broad hedge which fenced in the farm, and which was overgrown with briers and lichen. There he sat down to think about how it would go with him, if he never became a human being again. When father and mother came home from church, there would be a surprise for them. The whole township would come to stare at him. Perhaps father and mother would take him with them, and show him at the market place in Kivik. Birds of passage came on their travels. They travelled over the East sea, by way of Smygahuk, and were now on their way North. The wild geese, who came flying in two long rows, which met at an angle.

When the wild geese saw the tame geese, who walked about the farm, they sank nearer the earth, and called: “Come along! Come along! We're off to the hills!”

The tame geese could not resist the temptation to raise their heads and listen, but they answered very sensibly: “We're pretty well off where we are. We're pretty well off where we are.”

It was an uncommonly fine day, so light and bracing. And with each new wild geese-flock that flew by, the tame geese became more and more unruly. A couple of times they flapped their wings, but then an old mother-goose would always say to them: “Now don't be silly. Those creatures will have to suffer both hunger and cold.”

There was a young gander whom the wild geese had fired with a passion for adventure. “If another flock comes this way, I'll follow them,” said he.

Then there came a new flock, who shrieked like the others, and the young gander answered: “Wait a minute! Wait a minute! I'm coming.”

He spread his wings and raised himself into the air; but he was so unaccustomed to flying, that he fell to the ground again.

At any rate, the wild geese must have heard his call, for they turned and flew back slowly to see if he was coming.

“Wait, wait!” he cried, and made another attempt to fly. All this the boy heard, where he lay on the hedge. “It would be a great pity,” thought he, “if the big goosey-gander should go away. It would be a big loss to father and mother if he was gone.” When he thought of this, once again he entirely forgot that he was little and helpless. He took one leap right down into the goose-flock, and threw his arms around the neck of the goosey-gander. “Oh, no! You don't fly away this time, sir!” cried he.

But just about then, the gander was considering how he should go to work to raise himself from the ground. He couldn't stop to shake the boy off, hence he had to go along with him―up in the air.

They bore on toward the heights so rapidly, that the boy fairly gasped. Before he had time to think that he ought to let go his hold around the gander's neck, he was so high up that he would have been killed instantly, if he had fallen to the ground.

The only thing that he could do to make himself a little more comfortable, was to try and get upon the gander's back. And there he wriggled himself forthwith; but not without considerable trouble. And it was not an easy matter, either, to hold himself secure on the slippery back. He had to dig deep into feathers and down with both hands, to keep from tumbling to the ground.

THE BIG CHECKED CLOTH

The boy had grown so giddy that it was a long while before he came to himself. The winds howled and beat against him, and the rustle of feathers and swaying of wings sounded like a whole storm. Thirteen geese flew around him, flapping their wings and honking.

After a bit, he regained just enough sense to understand that he ought to find out where the geese were taking him. But this was not so easy, for he didn't know how he should ever muster up courage enough to look down. He was sure he'd faint if he attempted it.

The wild geese were not flying very high because the new travelling companion could not breathe in the very thinnest air. For his sake they also flew a little slower than usual.

At last the boy just made himself cast one glance down to earth. Then he thought that a great big rug lay spread beneath him, which was made up of an incredible number of large and small checks. “Where in all the world am I now?” he wondered.

He saw nothing but check upon check. Some were broad and ran crosswise, and some were long and narrow―all over, there were angles and corners. Nothing was round, and nothing was crooked. “What kind of a big, checked cloth is this that I'm looking down on?” said the boy to himself without expecting anyone to answer him.

But instantly the wild geese who flew about him called out: “Fields and meadows. Fields and meadows.”

Then he recognised that the bright green checks were rye fields. The yellowish-gray checks were stubble-fields―the remains of the oat-crop which had grown there the summer before. The brownish ones were old clover meadows: and the black ones, deserted grazing lands or ploughed-up fallow pastures.

The boy could not keep from laughing when he saw how checked everything looked. But when the wild geese heard him laugh, they called out―kind o’ reprovingly: “Fertile and good land. Fertile and good land.”

The boy had already become serious. “To think that you can laugh; you, who have met with the most terrible misfortune that can possibly happen to a human being!” thought he. And for a moment he was pretty serious; but it wasn't long before he was laughing again. Now that he had grown somewhat accustomed to the ride and the speed, so that he could think of something besides holding himself on the gander's back.

They came to one place where there were a number of big, clumsy-looking buildings with great, tall chimneys, and all around these were a lot of smaller houses. “This is Jordberga Sugar Refinery,” cried the roosters. The boy shuddered as he sat there on the goose's back. He ought to have recognised this place, for it was not very far from his home.

Here he had worked the year before as a watch boy; but, to be sure, nothing was exactly like itself when one saw it like that―from up above.

And think! Just think! Osa the goose girl and little Mats, who were his comrades last year! Indeed the boy would have been glad to know if they still were anywhere about here. Fancy what they would have said, had they suspected that he was flying over their heads!

Whenever the wild geese happened across any tame geese, they had the best fun! They flew forward very slowly and called down: “We're off to the hills. Are you coming along? Are you coming along?” But the tame geese answered: “It's still winter in this country. You're out too soon. Fly back! Fly back!”

The wild geese lowered themselves that they might be heard a little better, and called: “Come along! We'll teach you how to fly and swim.” Then the tame geese got mad and wouldn't answer them with a single honk.

The wild geese sank themselves still lower―until they almost touched the ground―then, quick as lightning, they raised themselves, just as if they'd been terribly frightened. “Oh, oh, oh!” they exclaimed. “Those things were not geese. They were only sheep, they were only sheep.” The ones on the ground were beside themselves with rage and shrieked.

When the boy heard all this teasing he laughed. Then he remembered how badly things had gone with him, and he cried. But the next second, he was laughing again.

精靈 三月二十日,星期日

從前,有個身材高瘦、動作敏捷的十四歲男孩,他沒什麼本事,成天喜歡做的事就是吃和睡,除此之外最愛調皮搗蛋。

星期日早晨,男孩的父母親正準備去教堂。男孩穿著襯衫,坐在桌邊,心想這下可好,爸媽都要出門,他有好幾個小時可以自由玩樂。「真棒!我可以把爸爸的槍拿下來把玩射擊,沒人管我。」

可是父親似乎猜中了男孩的心思,人都走到門口了,卻又停下來,轉身對他說:「你不和我們去教堂,至少要在家裡唸唸講道集。你願意嗎?」「願意,我一定會唸的。」男孩雖然嘴巴這麼說,心裡卻想著,如果他不想唸,當然就不會唸了。

男孩媽媽迅速地從壁爐邊的書架取下《路德講道集》,放在窗前的桌上,翻開當天要讀的那一篇。她還翻開《新約聖經》,放在講道集旁邊,最後把大扶手椅拖拉到桌前。

父親走到男孩身旁,嚴厲地說:「好好唸!我們回來時,我會一頁一頁地考你,要是你漏掉一頁沒唸,就有苦頭吃了。」

「這篇講道總共有十四頁半,」母親叮嚀。「你要馬上坐下來唸,不然會唸不完。」

他們說完就出門了。男孩在門口目送他們時,感覺好像中計了。「他們一定正在慶幸想了個好辦法,讓我在他們上教堂禮拜時不得不坐下來看書。」

可是他的父母親並沒有在慶幸什麼,反而相當苦惱。父親抱怨著兒子又笨又懶,上了學校也無心唸書,一點用處也沒有,連叫他看鵝都不放心。母親不否認這些批評,可是她最擔心的是兒子的頑劣。他會虐待動物,對人也不懷好意。母親說:「但願上帝讓他冷酷的心變得溫和!不然他會給他自己和我們招來不幸。」

男孩站了許久,考慮要不要去唸講道集。他終於得到結論:這次最好聽話。他坐進扶手椅,開始讀書。可是他低聲唸了一會兒,那咕咕噥噥的聲音似乎有催眠作用,讓他打起瞌睡。

外頭的天氣十分晴朗,木門半掩,在屋裡聽得見雲雀的啼唱。母雞和鵝群在院子裡漫步,牛隻也感覺到春天的氣息,不時哞哞叫著,表示嘉許。

男孩一邊讀書一邊打盹,與睡意搏鬥。「不行!我不可以睡。」他心想:「不然整個早上我都唸不完。」可他還是睡著了。

他不知道自己睡了多久,有一道輕微的響聲把他吵醒。

窗臺上的小鏡子正對著男孩,幾乎能從裡面看到整個屋內。男孩抬起頭來,正好看到鏡子,瞥見母親的衣箱蓋開著。

他的母親有一個束著鐵條的橡木箱,向來不准別人碰。裡面收藏著祖母留給她的物品,她非常愛惜那些東西。其中有幾件過時的農婦裝、漿好的白麻頭巾,以及沉甸甸的銀飾品。他母親也曾想要丟棄這些舊東西,卻又捨不得。

這時,男孩從鏡中清楚地看到箱蓋掀開著。他不明白怎麼會打開,因為他單獨在家時,母親絕不會讓那只珍貴的箱子開著。

他擔心是小偷溜進屋裡,他不敢動,只是靜靜坐著盯著鏡子。

他等著小偷現身時,看到箱子的邊緣有黑影。他一看再看,不敢相信自己的眼睛。那個起初像影子的東西變得越來越清晰,很快就看出那是個真的,是活生生的精靈―跨坐在箱子的邊緣上!

男孩確實聽說過精靈的故事,但是從沒想到他們竟然這麼小巧,坐在箱子邊的那個精靈不會比一隻手掌高。精靈有一張年老的臉,布滿皺紋,但沒有鬍鬚,身穿黑長袍、齊膝褲,戴著寬邊黑帽,他的衣著整齊美觀。他從箱子拿出一塊繡花布,坐在那裡端詳著上頭的舊式手工,沒有注意到男孩醒了。

男孩雖然感到驚訝,但一點也不害怕,那麼小的東西有什麼好怕的。何況精靈的神情專注,完全沒有察覺到四周的動靜。男孩心想,戲弄他應該很好玩,例如把他推進箱子,再闔上蓋子。

他一看見捕蝶網就伸手去拿,然後跳起來朝箱子邊緣揮過去。男孩根本不知道自己是怎麼辦到的,可是真的網住精靈了。可憐的小傢伙栽倒在網子深處,沒辦法掙脫。

起初男孩只是小心地搖晃網子,讓精靈無法站穩,也無法攀爬上來。

精靈可憐兮兮地求饒男孩釋放他。他說多年來一直在賜給男孩一家好運,男孩應該善待他。如果男孩肯放他走,他願意給他一枚舊硬幣、一把銀湯匙和一個像他父親的銀錶一樣大的金幣。

男孩覺得精靈承諾的東西不算多,可是捉到精靈之後,他開始害怕了,覺得自己正跟不屬於這個世界的怪異東西打交道,他很樂意擺脫精靈,馬上答應這筆交易。他停止搖晃網子,讓精靈爬出來。可是當精靈幾乎要爬出網子時,男孩又想到應該要求更多財富和好東西,至少應該要求精靈把講道集的內容塞進他的腦子裡。「我真笨,怎麼能讓他跑掉!」這麼想著,他開始粗魯地搖晃網子,所以精靈又跌了下來。

瞬間,男孩挨了個結實的巴掌,覺得整顆頭都要碎掉了。他被甩出去,從一面牆撞到另一面牆,最後倒地不起,失去意識。

醒來時,屋裡只有他一個人。箱蓋是闔上的,捕蝶網好端端地掛在窗邊。要不是頭和臉頰因為挨了耳光而感到熱辣,他會相信是一場夢。「無論如何,爸媽都會認為我是在做夢。」他心想:「他們絕不會因為精靈而饒過我沒唸講道集,我最好趕快開始唸。」

可是當他起身要走到桌邊時,發覺事情不太對勁。屋子不可能變大,但為什麼桌子變得比平常還要遠呢?那把椅子又是怎麼一回事?它看起來不會比之前大,可是他卻得踩著底下的橫桿,才能爬上座位。桌子也是一樣,他必須爬上椅子扶手,才看得到桌面。

「發生什麼事了?」男孩說。「一定是精靈對桌子和椅子,還有整個屋子都施了魔法。」

講道集仍放在桌上,看似無異,可是一定有哪裡有問題,因為他如果不站在書上,就一個字也看不到。

他唸了幾行字後不經意地抬起頭,視線落到鏡子,馬上大叫:「哎!那還有一個!」鏡中有個戴著帽兜,穿著皮褲的小傢伙。

「啊,他的穿著和我一模一樣。」男孩說,他吃驚得拍著雙手。這時他看到鏡子裡的人也做出同樣的動作。他拉拉頭髮,捏捏手臂,扭動身體,鏡子裡的人都馬上照做。

男孩繞著鏡子跑了幾圈,看看有沒有小人藏在後面,可是什麼也沒發現。他開始嚇得全身發抖,現在他明白了,那個精靈對他施了魔法,鏡子裡的影像就是他自己。

野鵝

男孩無法相信自己變成精靈了。他想著:「這一定是一場夢,等一下我就會變回人類了。」

他站在鏡子前,閉上眼睛,希望幾分鐘後睜開眼睛時,一切都已過去。但事與願違,他的個子還是那麼小。就某方面來說,他和之前沒有兩樣。淡黃色的頭髮、遍布鼻子的雀斑、皮褲和襪子上的補丁都和之前相同,唯一的差別是全部都縮小了。

他可以確定,站在這裡等再久也沒用,必須想想辦法,而他想到的最聰明的辦法是去找那個精靈,和他講和。

男孩一邊哭一邊祈禱,答應做到所有他想得到的事。再也不說話不算話、惡作劇,或是在聽講道時睡著。只要他能夠變回人類,他願意成為樂於助人的乖孩子。可是無論他怎麼許願,都沒有用。

突然之間,他記起來曾經聽母親說過,精靈都住在牛棚裡,就決定去那邊看看。幸好屋子的門半開著,不然他根本搆不到門拴。他輕易地從門口溜出去。

他來到門廊,尋找他的木鞋,因為他在屋裡只穿著襪子,正想著要如何穿上那雙笨重的大鞋時,看到門階上有一雙小鞋。精靈竟然設想周到,對木鞋也施了魔法。這下子他更不安了,因為精靈顯然要折磨他很久。

有隻灰色的麻雀在屋子前面的木頭地板上跳躍。他一看到男孩就大叫:「啾啾!啾啾!看這個呆頭男孩尼爾斯!看這個拇指大的尼爾斯‧霍爾加松!」

院子裡的鵝和雞都轉過頭來看,然後發出嚇人的咯咯聲。公雞喊道:「活該!咕咕咕!他扯過我的雞冠!」母雞也一起叫著:「活該!」鵝聚在一起,抬頭問道:「是誰讓他變成這樣的?」

奇怪的是,男孩聽得懂他們的話。他吃驚地站在門階上聽,同時自言自語:「一定是因為我變成精靈了,所以聽得懂鳥語。」

他受不了母雞一直說他活該,就朝他們扔出一顆石頭,大吼:「閉嘴,你們這群畜生!」

可是母雞不再怕他了,整群母雞衝過去,圍著他,出聲叫罵:「你活該!你活該!」

男孩想要逃跑,雞群卻在後面追著,直到他覺得耳朵快要聾了。要是他們家的貓沒有走過來,也許他永遠也擺脫不了。雞群一看到貓就安靜下來,假裝只是在啄地上的蚯蚓。

男孩迅速跑到貓那裡說:「親愛的貓咪!你一定知道這一帶所有躲藏的地方吧?乖小貓,告訴我哪裡可以找到精靈?」

貓咪沒有立即回答。他悠閒地坐下來,尾巴優雅地在腳掌上圍成圈,兩眼瞪著男孩。那是隻大黑貓,胸前有一塊白斑,毛皮光滑、柔軟,在日光下顯出光澤。他的爪子內縮,暗灰色的瞳孔瞇成細縫,看起來很溫馴。

「我知道精靈在哪裡,」貓咪柔聲說,「但我不會告訴你。」

「親愛的貓咪,你一定要告訴我!」男孩哀求。「你看不出他對我施了魔法嗎?」

貓的眼睛微睜,透出一道寒光。他轉了一圈,發出滿足的呼嚕聲,然後回答:「就因為你經常拉我的尾巴,所以我要幫你嗎?」

男孩生起氣來,忘記自己已經變小了。「哦!那我要再去拉你的尾巴。」他說著,跑向那隻貓。

那隻貓一轉眼豎起每一根毛髮,拱著背,伸長四肢,爪子在地上刮搔,尾巴變得又粗又短,耳朵往後縮,口吐唾沫,睜大的眼睛閃現火花似的光芒。

男孩不想對貓示弱,就又向前一步。貓跳起來撲向男孩,把男孩推倒,前腳按著他的胸部,張大的嘴巴對著他的喉嚨。

男孩感覺到銳利的爪子穿透他的衣服,刺進皮膚,犬齒碰到他的喉嚨。他盡可能大喊救命,卻沒有人過來。以為自己一定沒命了,卻發覺貓縮回爪子,把他放開。

「看在女主人的份上,放你一馬。我只是讓你知道,現在我們兩個之間誰比較佔上風。」貓說完就走開了,變回和之前一樣溫和。男孩羞愧得說不出話來,只好趕緊去牛棚找精靈。

那裡有三頭牛,年紀都很大了。可是男孩一進來,就引起一陣怒吼和騷動,足以讓人以為裡面至少養了三十頭牛。

「哞,哞,哞,」三頭牛一起叫喊。男孩聽不清楚他們說什麼,因為一隻比一隻吼得更大聲。

男孩想問精靈的事,可是聲音進不去他們的耳裡。就像之前他把陌生的狗放進去時一樣,他們猛踢後腿,搖晃側腹,頭伸直,牛角對準了男孩。

「過來!」五月玫瑰說。「我要踢你一腳,讓你難以忘記!」

「過來,」金百合說。「我要你在我的角上跳舞!」

「過來,去年夏天你用木鞋扔我,我要讓你嚐嚐那是什麼滋味!」星星說。

五月玫瑰是年紀最大、最聰明,也是最生氣的。「你過來,我要讓你吃點苦頭,因為你曾經多次害你媽媽打翻牛奶桶,也因為你,她常常站在這裡為你掉眼淚。」

男孩很想跟他們說,他很後悔做了那些壞事,以後一定會乖乖的,只要告訴他精靈在哪裡。可是那三頭牛不肯聽他說話,不斷叫罵,男孩害怕他們會掙脫繩子,覺得現在最好安靜地離開牛棚。

男孩沮喪地走出來,他知道這裡不會有人願意幫他找到精靈。他爬到農場圍牆上,想著如果不能變回人類會怎樣。爸媽從教堂回來時一定會很吃驚。消息會傳到全國,人們會從四面八方跑來看他。也許爸媽會帶他到城市的市場供人觀賞。候鳥乘風飛行,穿越波羅的海飛向北方。野鵝排成人字形飛著。

野鵝看到在農場漫步的家鵝時,就會飛近地面大叫:「一起來吧!一起飛向高山!」家鵝都不禁抬頭傾聽,可是都理智地回答:「我們在這裡過得很好。」

這天的天氣特別晴朗怡人,隨著一群群野鵝飛過,家鵝變得越來越興奮。有時他們會拍動翅膀,但總是有一隻母鵝跟他們說:「別傻了,跟著那些傢伙會挨餓受凍的!」

有隻年輕的鵝名叫莫爾登,對旅行產生憧憬。他說:「要是再有一群飛過來,我就要跟他們走。」

真的又來了一群野鵝,和之前的鵝群一樣大聲叫喊,年輕的公鵝莫爾登回答:「等一等,等一等,我來了。」

他張開翅膀,升到空中,可是他不習慣飛行,很快就掉下來。

儘管如此,野鵝們聽見了公鵝莫爾登的叫聲,就折回來慢慢飛,看他有沒有跟來。

「等一等!」莫爾登再度嘗試飛起來。男孩坐在圍牆上,每句話都聽見了。他心想:「如果這隻大公鵝飛走了,對爸媽來說是很大的損失。」光想到這一點,他便忘了自己有多弱小,跳起來用雙臂抱住公鵝的脖子。「不行,你這次先別走。」他大叫。

公鵝正想著如何騰空飛起,來不及甩掉男孩,就帶著他飛到空中了。

他們一下子就飛到高空,男孩倒抽一口氣,才剛覺得可以把手放開時,已經離地面很高,掉到地上一定會沒命。

唯一能做的就是讓自己舒服一點,所以他騎到公鵝的背上,把手插進羽毛中抓緊,才不會摔下來。

大方格布

男孩覺得頭暈眼花,過了很久才恢復神智。風呼嘯而過,羽毛的沙沙聲和拍動翅膀的聲音聽起來彷彿暴風。十三隻鵝飛在他旁邊,一邊振翅一邊呱呱叫著。

過了一會兒他才清醒過來,覺得應該問問鵝群要帶他去哪裡。可是並不容易,因為他不敢往下看,他確信自己一看就會頭暈。

野鵝飛得並不高,因為新夥伴無法在稀薄的空氣中呼吸。也因為這樣,他們飛得比平常緩慢。

男孩朝底下瞥了一眼,感覺好像鋪著一大塊布,由許多大小不同的格子拼湊而成。「我到底是在哪裡?」他很想知道。

他只看到一塊塊格子。有的是菱形,有的是長方形,沒有一個是圓的或彎的。「下面這塊大方格布到底是什麼呢?」他自言自語,並不指望聽到回答。

可是圍在他旁邊的野鵝隨即喊道:「田地和草地。」

他這才認出鮮綠色的格子是裸麥田,灰黃色的格子是去年夏天收割完的田地,褐色的是老苜蓿地,黑色的是廢棄的放牧地或犁過的休耕地。

男孩看到一切都變成格子時,不禁哈哈大笑。可是野鵝聽到他的笑聲,就以斥責的口氣大喊:「肥美的土地!」

男孩正經起來,心想:「你居然還笑得出來,想想是誰遇到了一個人類所能遇到最悲慘的事!」他嚴肅了一會兒,但不久又笑了出來。他習慣了騎鵝和飛行速度,可以一邊抓著鵝背一邊想事情。

他們經過一些裝著高大煙囪的笨拙建築,四周有許多小房子。「這裡是糖廠。」公雞群嚷著。男孩在鵝背上吃了一驚。他認得這裡,因為離他家不遠。

去年曾來這裡打工,不過從上面看起來,全部都變了樣。

當時他認識了看鵝女孩歐莎和小麥茲,很想知道他們是否還在這裡。要是他們知道他正在飛過他們的頭頂,不知道會怎麼說!

野鵝從家鵝頭上飛過去時是最快樂的!他們會飛得很慢,同時往下叫喊:「我們要飛到山上。你們要一起來嗎?」但家鵝回答:「這國家還是冬天,你們太早出國了。飛回來!飛回來!」

野鵝們飛得更低了,好讓底下的鵝聽得更清楚。「一起來!我們會教你們飛行和游泳。」家鵝生氣了,不肯再回答。

野鵝們飛得越來越低,幾乎要碰到地面,然後快如閃電地升空,彷彿受到驚嚇。「哎唷,哎唷!」他們大叫。「這些傢伙不是鵝,他們只是羊,只是羊。」地上的鵝聽了都氣壞了,紛紛叫罵。

男孩聽見這番嘲諷時笑了,但想起身上的惡運,又哭了起來。但過沒多久又笑了。

01 THE BOY

THE ELF Sunday, March twentieth.

Once there was a boy. He was―let us say―something like fourteen years old; long and loose-jointed. He wasn't good for much. His chief delight was to eat and sleep; and after that―he liked best to make mischief.

It was a Sunday morning and the boy's parents were getting ready to go to church. The boy sat on the edge of the table, in his shirt sleeves, and thought how lucky it was that both father and mother were going away, and the coast would be clear for a couple of hours. “Good! Now I can take down pop's gun and fire off a shot, without anybody's meddling interference,” he said to himself.

But it was almost as if father should have guessed the boy's thoughts, for just as he was on the threshold―ready to start―he stopped short, and turned toward the boy. “Since you won't come to church with mother and me,” he said, “the least you can do, is to read the service at home. Will you promise to do so?” “Yes,” said the boy, “that I can do easy enough.” And he thought, of course, that he wouldn't read any more than he felt like reading.

In a second his mother was over by the shelf near the fireplace, and took down Luther's Commentary and laid it on the table, in front of the window―opened at the service for the day. She also opened the New Testament, and placed it beside the Commentary. Finally, she drew up the big arm-chair.

His father walked up to the boy, and said in a severe tone: “Remember, that you are to read carefully! For when we come back, I shall question you thoroughly; and if you have skipped a single page, it will not go well with you.”

“The service is fourteen and a half pages long,” said his mother. “You'll have to sit down and begin the reading at once, if you expect to get through with it.”

With that they departed. And as the boy stood in the doorway watching them, he thought that he had been caught in a trap. “There they go congratulating themselves, I suppose, in the belief that they've hit upon something so good that I'll be forced to sit and hang over the sermon the whole time that they are away,” thought he.

But his father and mother were certainly not congratulating themselves upon anything of the sort; but, on the contrary, they were very much distressed. Father complained that he was dull and lazy; he had not cared to learn anything at school, and he was such an all-round good-for-nothing, that he could barely be made to tend geese. Mother did not deny that; but she was most distressed because he was wild and bad; cruel to animals, and ill-willed toward human beings. “May God soften his hard heart, and give him a better disposition!” said the mother, “or else he will be a misfortune, both to himself and to us.”

The boy stood for a long time and pondered whether he should read the service or not. Finally, he came to the conclusion that, this time, it was best to be obedient. He seated himself in the easy chair, and began to read. But when he had been rattling away in an undertone for a little while, this mumbling seemed to have a soothing effect upon him―and he began to nod.

It was the most beautiful weather outside! The cottage door stood ajar, and the lark's trill could be heard in the room. The hens and geese pattered about in the yard, and the cows, who felt the spring air away in their stalls, lowed their approval every now and then.

The boy read and nodded and fought against drowsiness. “No! I don't want to fall asleep,” thought he, “for then I'll not get through with this thing the whole forenoon.” But―somehow―he fell asleep.

He did not know whether he had slept a short while, or a long while; but he was awakened by hearing a slight noise back of him.

On the window-sill, facing the boy, stood a small looking-glass; and almost the entire cottage could be seen in this. As the boy raised his head, he happened to look in the glass; and then he saw that the cover to his mother's chest had been opened.

His mother owned a great, heavy, iron-bound oak chest, which she permitted no one but herself to open. Here she treasured all the things she had inherited from her mother, and of these she was especially careful. Here lay a couple of old-time peasant dresses, and starched white-linen head-dresses, and heavy silver ornaments and chains. Several times his mother had thought of getting rid of the old things; but somehow, she hadn't had the heart to do it.

Now the boy saw distinctly―in the glass―that the chest-lid was open. He could not understand how this had happened. She never would have left that precious chest open when he was at home, alone.

He was afraid that a thief had sneaked his way into the cottage. He didn't dare to move; but sat still and stared into the looking-glass.

While he waited for the thief to make his appearance, he began to wonder what that dark shadow was which fell across the edge of the chest. He looked and looked―and did not want to believe his eyes. But the thing, which at first seemed shadowy, became more and more clear to him; and soon he saw that it was something real. It was no less a thing than an elf who sat there―astride the edge of the chest!

To be sure, the boy had heard stories about elves, but he had never dreamed that they were such tiny creatures. He was no taller than a hand's breadth―this one, who sat on the edge of the chest. He had an old, wrinkled and beardless face, and was dressed in a black frock coat, knee-breeches and a broad-brimmed black hat. He was very trim and smart. He had taken from the chest an embroidered piece, and sat and looked at the old-fashioned handiwork with such an air of veneration, that he did not observe the boy had awakened.

The boy was surprised to see the elf, but he was not particularly frightened. It was impossible to be afraid of one who was so little. And since the elf was so absorbed in his own thoughts that he neither saw nor heard, the boy thought that it would be great fun to play a trick on him; to push him over into the chest and shut the lid on him, or something of that kind.

He had hardly set eyes on that butterfly-snare, before he reached over and snatched it and jumped up and swung it alongside the edge of the chest. He hardly knew how he had managed it―but he had actually snared the elf. The poor little chap lay, head downward, in the bottom of the long snare, and could not free himself.

The first moment the boy was only particular to swing the snare backward and forward; to prevent the elf from getting a foothold and clambering up.

The elf began to begged, oh! so pitifully, for his freedom. He had brought them good luck―these many years―he said, and deserved better treatment. Now, if the boy would set him free, he would give him an old coin, a silver spoon, and a gold penny, as big as the case on his father's silver watch.

The boy didn't think that this was much of an offer; but it so happened―that after he had gotten the elf in his power, he was afraid of him. He felt that he had entered into an agreement with something weird and uncanny; something which did not belong to his world, and he was only too glad to get rid of the horrid thing. For this reason he agreed at once to the bargain, and held the snare still, so the elf could crawl out of it. But when the elf was almost out of the snare, the boy happened to think that he ought to have bargained for large estates, and all sorts of good things. He should at least have made this stipulation: that the elf must conjure the sermon into his head. “What a fool I was to let him go!” thought he, and began to shake the snare violently, so the elf would tumble down again.

But the instant the boy did this, he received such a stinging box on the ear, that he thought his head would fly in pieces. He was dashed―first against one wall, then against the other; he sank to the floor, and lay there―senseless.

When he awoke, he was alone in the cottage. The chest-lid was down, and the butterfly-snare hung in its usual place by the window. If he had not felt how the right cheek burned, from that box on the ear, he would have been tempted to believe the whole thing had been a dream. “At any rate, father and mother will be sure to insist that it was nothing else,” thought he. “They are not likely to make any allowances for that old sermon, on account of the elf. It's best for me to get at that reading again,” thought he.

But as he walked toward the table, he noticed something remarkable. It couldn't be possible that the cottage had grown. But why was he obliged to take so many more steps than usual to get to the table? And what was the matter with the chair? It looked no bigger than it did a while ago; but now he had to step on the rung first, and then clamber up in order to reach the seat. It was the same thing with the table. He could not look over the top without climbing to the arm of the chair.

“What in all the world is this?” said the boy. “I believe the elf has bewitched both the armchair and the table―and the whole cottage.”

The Commentary lay on the table and, to all appearances, it was not changed; but there must have been something queer about that too, for he could not manage to read a single word of it, without actually standing right in the book itself.

He read a couple of lines, and then he chanced to look up. With that, his glance fell on the looking-glass; and then he cried aloud: “Look! There's another one!” For in the glass he saw plainly a little, little creature who was dressed in a hood and leather breeches.

“Why, that one is dressed exactly like me!” said the boy, and clasped his hands in astonishment. But then he saw that the thing in the mirror did the same thing. Then he began to pull his hair and pinch his arms and swing round; and instantly he did the same thing after him; he, who was seen in the mirror.

The boy ran around the glass several times, to see if there wasn't a little man hidden behind it, but he found no one there; and then he began to shake with terror. For now he understood that the elf had bewitched him, and that the creature whose image he saw in the glass―was he, himself.

THE WILD GEESE

The boy simply could not make himself believe that he had been transformed into an elf. “It can't be anything but a dream. If I wait a few moments, I'll surely be turned back into a human being again.”

He placed himself before the glass and closed his eyes. He opened them again after a couple of minutes, and then expected to find that it had all passed over―but it hadn't. He was―and remained―just as little. In other respects, he was the same as before. The thin, straw-coloured hair; the freckles across his nose; the patches on his leather breeches and the darns on his stockings, were all like themselves, with this exception―that they had become diminished.

No, it would do no good for him to stand still and wait, of this he was certain. He must try something else. And he thought the wisest thing that he could do was to try and find the elf, and make his peace with him.

He cried and prayed and promised everything he could think of. Nevermore would he break his word to anyone; never again would he be naughty; and never, never would he fall asleep again over the sermon. If he might only be a human being once more, he would be such a good and helpful and obedient boy. But no matter how much he promised―it did not help him the least little bit.

Suddenly he remembered that he had heard his mother say, all the tiny folk made their home in the cowsheds; and, at once, he concluded to go there, and see if he couldn't find the elf. It was a lucky thing that the cottage-door stood partly open, for he never could have reached the bolt and opened it; but now he slipped through without any difficulty.

When he came out in the hallway, he looked around for his wooden shoes; for in the house, to be sure, he had gone about in his stocking-feet. He wondered how he should manage with these big, clumsy wooden shoes; but just then, he saw a pair of tiny shoes on the doorstep. When he observed that the elf had been so thoughtful that he had also bewitched the wooden shoes, he was even more troubled. It was evidently his intention that this affliction should last a long time.

On the wooden board-walk in front of the cottage, hopped a gray sparrow. He had hardly set eyes on the boy before he called out: “Teetee! Teetee! Look at Nils goosey-boy! Look at Thumbietot! Look at Nils Holgersson Thumbietot!”

Instantly, both the geese and the chickens turned and stared at the boy; and then they set up a fearful cackling. “Good enough for him! Cock-el-i-coo, he has pulled my comb.” crowed the rooster. “Serves him right!” cried the hens. The geese got together in a tight group, stuck their heads together and asked: “Who can have done this?”

But the strangest thing of all was, that the boy understood what they said. He was so astonished, that he stood there as if rooted to the doorstep, and listened. “It must be because I am changed into an elf,” said he. “This is probably why I understand bird-talk.”

He thought it was unbearable that the hens would not stop saying that it served him right. He threw a stone at them and shouted:

“Shut up, you pack!”

However, he was no longer the sort of boy the hens need fear. The whole henyard made a rush for him, and formed a ring around him; then they all cried at once: “Served you right! Ka, ka, kada, served you right!”

The boy tried to get away, but the chickens ran after him and screamed, until he thought he'd lose his hearing. It is more than likely that he never could have gotten away from them, if the house cat hadn't come along just then. As soon as the chickens saw the cat, they quieted down and pretended to be thinking of nothing else than just to scratch in the earth for worms.

Immediately the boy ran up to the cat. “You dear pussy!” said he, “you must know all the corners and hiding places about here? You'll be a good little kitty and tell me where I can find the elf.”

The cat did not reply at once. He seated himself, curled his tail into a graceful ring around his paws―and stared at the boy. It was a large black cat with one white spot on his chest. His fur lay sleek and soft, and shone in the sunlight. The claws were drawn in, and the eyes were a dull gray, with just a little narrow dark streak down the centre. The cat looked thoroughly good-natured and inoffensive.

“I know well enough where the elf lives,” he said in a soft voice, “but I'm not going to tell you that.”

“Dear pussy, you must tell me where the elf lives!” said the boy. “Can't you see how he has bewitched me?”

The cat opened his eyes a little, so that the green wickedness began to shine forth. He spun round and purred with satisfaction before he replied. “Shall I perhaps help you because you have so often grabbed me by the tail?” he said at last.

Then the boy was furious and forgot entirely how little and helpless he was now. “Oh! I can pull your tail again, I can,” said he, and ran toward the cat.

The next instant the hair on the cat's body stood on end. The back was bent; the legs had become elongated; the claws scraped the ground; the tail had grown thick and short; the ears were laid back; the mouth was frothy; and the eyes were wide open and glistened like sparks of red fire.

The boy didn't want to let himself be scared by a cat, and he took a step forward. Then the cat made one spring and landed right on the boy; knocked him down and stood over him―his forepaws on his chest, and his jaws wide apart―over his throat.

The boy felt how the sharp claws sank through his vest and shirt and into his skin; and how the sharp eye-teeth tickled his throat. He shrieked for help, as loudly as he could, but no one came. He thought surely that his last hour had come. Then he felt that the cat drew in his claws and let go the hold on his throat.

“I'll let you go this time, for my mistress's sake. I only wanted you to know which one of us two has the power now.” With that the cat walked away―looking as smooth and pious as he did when he first appeared on the scene. The boy was so crestfallen that he didn't say a word, but only hurried to the cowhouse to look for the elf.

There were not more than three cows, all told. But when the boy came in, there was such a bellowing and such a kick-up, that one might easily have believed that there were at least thirty.

“Moo, moo, moo,” sang the three of them in unison. He couldn't hear what they said, for each one tried to out-bellow the others.

The boy wanted to ask after the elf, but he couldn't make himself heard because the cows were in full uproar. They carried on as they used to do when he let a strange dog in on them. They kicked with their hind legs, shook their necks, stretched their heads, and measured the distance with their horns.

“Come here!” said Mayrose, “and you'll get a kick that you won't forget in a hurry!”

“Come here,” said Gold Lily, “and you shall dance on my horns!”

“Come here, and you shall taste how it felt when you threw your wooden shoes at me, as you did last summer!” bawled Star.

Mayrose was the oldest and the wisest of them, and she was the very maddest. “Come here!” said she, “that I may pay you back for the many times that you have jerked the milk pail away from your mother; and for all the tears when she has stood here and wept over you!”

The boy wanted to tell them how he regretted that he had been unkind to them; and that never, never―from now on―should he be anything but good, if they would only tell him where the elf was. But the cows didn't listen to him. They made such a racket that he began to fear one of them would succeed in breaking loose; and he thought that the best thing for him to do was to go quietly away from the cowhouse.

When he came out, he was thoroughly disheartened. He could understand that no one on the place wanted to help him find the elf. He crawled up on the broad hedge which fenced in the farm, and which was overgrown with briers and lichen. There he sat down to think about how it would go with him, if he never became a human being again. When father and mother came home from church, there would be a surprise for them. The whole township would come to stare at him. Perhaps father and mother would take him with them, and show him at the market place in Kivik. Birds of passage came on their travels. They travelled over the East sea, by way of Smygahuk, and were now on their way North. The wild geese, who came flying in two long rows, which met at an angle.

When the wild geese saw the tame geese, who walked about the farm, they sank nearer the earth, and called: “Come along! Come along! We're off to the hills!”

The tame geese could not resist the temptation to raise their heads and listen, but they answered very sensibly: “We're pretty well off where we are. We're pretty well off where we are.”

It was an uncommonly fine day, so light and bracing. And with each new wild geese-flock that flew by, the tame geese became more and more unruly. A couple of times they flapped their wings, but then an old mother-goose would always say to them: “Now don't be silly. Those creatures will have to suffer both hunger and cold.”

There was a young gander whom the wild geese had fired with a passion for adventure. “If another flock comes this way, I'll follow them,” said he.

Then there came a new flock, who shrieked like the others, and the young gander answered: “Wait a minute! Wait a minute! I'm coming.”

He spread his wings and raised himself into the air; but he was so unaccustomed to flying, that he fell to the ground again.

At any rate, the wild geese must have heard his call, for they turned and flew back slowly to see if he was coming.

“Wait, wait!” he cried, and made another attempt to fly. All this the boy heard, where he lay on the hedge. “It would be a great pity,” thought he, “if the big goosey-gander should go away. It would be a big loss to father and mother if he was gone.” When he thought of this, once again he entirely forgot that he was little and helpless. He took one leap right down into the goose-flock, and threw his arms around the neck of the goosey-gander. “Oh, no! You don't fly away this time, sir!” cried he.

But just about then, the gander was considering how he should go to work to raise himself from the ground. He couldn't stop to shake the boy off, hence he had to go along with him―up in the air.

They bore on toward the heights so rapidly, that the boy fairly gasped. Before he had time to think that he ought to let go his hold around the gander's neck, he was so high up that he would have been killed instantly, if he had fallen to the ground.

The only thing that he could do to make himself a little more comfortable, was to try and get upon the gander's back. And there he wriggled himself forthwith; but not without considerable trouble. And it was not an easy matter, either, to hold himself secure on the slippery back. He had to dig deep into feathers and down with both hands, to keep from tumbling to the ground.

THE BIG CHECKED CLOTH

The boy had grown so giddy that it was a long while before he came to himself. The winds howled and beat against him, and the rustle of feathers and swaying of wings sounded like a whole storm. Thirteen geese flew around him, flapping their wings and honking.

After a bit, he regained just enough sense to understand that he ought to find out where the geese were taking him. But this was not so easy, for he didn't know how he should ever muster up courage enough to look down. He was sure he'd faint if he attempted it.

The wild geese were not flying very high because the new travelling companion could not breathe in the very thinnest air. For his sake they also flew a little slower than usual.

At last the boy just made himself cast one glance down to earth. Then he thought that a great big rug lay spread beneath him, which was made up of an incredible number of large and small checks. “Where in all the world am I now?” he wondered.

He saw nothing but check upon check. Some were broad and ran crosswise, and some were long and narrow―all over, there were angles and corners. Nothing was round, and nothing was crooked. “What kind of a big, checked cloth is this that I'm looking down on?” said the boy to himself without expecting anyone to answer him.

But instantly the wild geese who flew about him called out: “Fields and meadows. Fields and meadows.”

Then he recognised that the bright green checks were rye fields. The yellowish-gray checks were stubble-fields―the remains of the oat-crop which had grown there the summer before. The brownish ones were old clover meadows: and the black ones, deserted grazing lands or ploughed-up fallow pastures.

The boy could not keep from laughing when he saw how checked everything looked. But when the wild geese heard him laugh, they called out―kind o’ reprovingly: “Fertile and good land. Fertile and good land.”

The boy had already become serious. “To think that you can laugh; you, who have met with the most terrible misfortune that can possibly happen to a human being!” thought he. And for a moment he was pretty serious; but it wasn't long before he was laughing again. Now that he had grown somewhat accustomed to the ride and the speed, so that he could think of something besides holding himself on the gander's back.

They came to one place where there were a number of big, clumsy-looking buildings with great, tall chimneys, and all around these were a lot of smaller houses. “This is Jordberga Sugar Refinery,” cried the roosters. The boy shuddered as he sat there on the goose's back. He ought to have recognised this place, for it was not very far from his home.

Here he had worked the year before as a watch boy; but, to be sure, nothing was exactly like itself when one saw it like that―from up above.

And think! Just think! Osa the goose girl and little Mats, who were his comrades last year! Indeed the boy would have been glad to know if they still were anywhere about here. Fancy what they would have said, had they suspected that he was flying over their heads!

Whenever the wild geese happened across any tame geese, they had the best fun! They flew forward very slowly and called down: “We're off to the hills. Are you coming along? Are you coming along?” But the tame geese answered: “It's still winter in this country. You're out too soon. Fly back! Fly back!”

The wild geese lowered themselves that they might be heard a little better, and called: “Come along! We'll teach you how to fly and swim.” Then the tame geese got mad and wouldn't answer them with a single honk.

The wild geese sank themselves still lower―until they almost touched the ground―then, quick as lightning, they raised themselves, just as if they'd been terribly frightened. “Oh, oh, oh!” they exclaimed. “Those things were not geese. They were only sheep, they were only sheep.” The ones on the ground were beside themselves with rage and shrieked.

When the boy heard all this teasing he laughed. Then he remembered how badly things had gone with him, and he cried. But the next second, he was laughing again.

主題書展

更多

主題書展

更多書展今日66折

您曾經瀏覽過的商品

購物須知

為了保護您的權益,「三民網路書店」提供會員七日商品鑑賞期(收到商品為起始日)。

若要辦理退貨,請在商品鑑賞期內寄回,且商品必須是全新狀態與完整包裝(商品、附件、發票、隨貨贈品等)否則恕不接受退貨。