商品簡介

相關商品

商品簡介

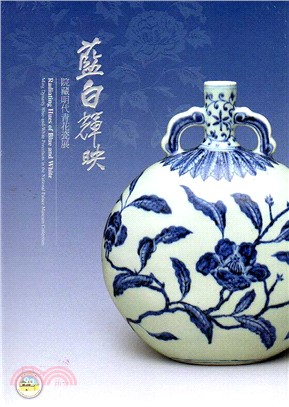

文化因交流的激盪,產生新的生命力。亞洲文明間的藝術文化,從相遇、激盪、挪借、再創的種種現象不斷發生,若論其中與人印象最深刻的,應屬青花瓷器;而歐洲人心目中的亞洲意象裡,藍白輝映的青花瓷器也必包含其中。這是國立故宮博物院將「藍白輝映-院藏明代青花瓷展」列為南院開幕首展的主因;當然另一重要因素是:本院所藏明代青花瓷享譽世界。 中國白瓷在七世紀傳入西亞,西亞沒有瓷土,但複製出錫白釉的陶器,還以該地含氧化鈷的顏料描繪出藍色圖畫。這種藍白圖樣的陶器也出現在中國唐代窯廠裡,但在外國釉藥難求後就停頓了。到了十四世紀中期,元朝引入外來顏料至景德鎮,遂燒造出神彩飛揚的元青花,也為明清官窯持續燒造的重要瓷器類型,並進而藉著賞賜餽贈關係,成為亞洲各重要王朝的珍品。周邊國家如朝鮮、越南、土耳其也在該國設官窯,創燒青花圖案的陶瓷器,許多圖案明顯受到中國瓷器的影響。當歐洲勢力來到亞洲,他們清楚感受到亞洲青花陶瓷之美,也在歐洲創燒歐洲式的青花器皿,帶著濃厚的亞洲意象。這項複雜的青花發展史,在不同時期多路線來回往復的流通與啟發,成為早期全球化美感疊生的重要現象。 明代官窯青花瓷在全球青花瓷中佔有重要位置。基本上,官窯非為貿易而生,卻成為各國爭相來朝貢以便換取賞賜的物件,品質精良絕倫是明青花的魅力。明朝政府不惜工本,以國家經費、調撥工匠、嚴格督驗下大量燒造青花瓷器;為了賞賜需求,瓷器造形大量取自中亞金屬器,紋樣也引入異域的新元素。明朝內廷畫家參與瓷器紋樣的設計,青花顏料則幾度取用中亞的礦物,所製作的瓷器已是泛亞洲元素的組合。 明代朝廷瞭解青花瓷最能清楚表現官方樣式,觀明青花如觀明朝帝王的想望。如五爪龍是皇室威權象徵,雲鶴神仙是嘉靖的道教信仰,藏文咒詞能見明廷與藏傳佛教的密切,阿拉伯文字書寫正德皇帝的祈禱。不同青料則讓永宣青花如淋漓渲暢的潑墨畫,成化青花淡雅如文人小品,嘉萬青花為豔麗的變形畫派。因此,院藏明青花的特展裡,以年代序列將明青花分「洪武至宣德」、「正統至正德」、「嘉靖至明末」三個段落展出,讓青花瓷傳達明代的歷史發展,及其如何融入亞洲文明元素。第四單元則陳列受明青花影響的越南、朝鮮、日本、波斯等亞洲生產的青花瓷,呈現藍白潮流於各地不同的發展風貌;本院亞洲瓷器收藏,除中國外其他數量尚在起步階段,但已可勾勒出明時代各地青花瓷所共同烘顯的亞洲世界。本次展覽,是器物處處長蔡玫芬與南院處翁宇雯助理研究員共同策展,宇雯負責選件與說明,經蔡處長調整選件與審定論述,並分別撰寫〈陶政與官樣-兼述國立故宮博物院藏明代青花瓷〉與〈明時期亞洲各地誕生的青花瓷器〉兩文,加強圖錄論述。「藍白輝映-院藏明代青花瓷展」是本院首次以青花瓷為題,全面呈現院藏明代青花瓷之美,並以青花瓷作媒介,說明亞洲各地文化交流現象。 青花瓷發祥於中國,流傳廣泛,影響深遠。瓷胎潔白光亮,藍白輝映精緻細膩的紋飾,是生活美學的極致表現,迄今仍為世人喜愛。

Radiating Hues of Blue and White: Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Porcelains in the National Palace Museum Collection Cultures receive new impetus by interacting with each other. In Asia, we have witnessed many encounters, cross-fertilizations, borrowings, and re-creations between arts and cultures, and underglaze blue porcelain is a prime example. When Europeans think of Asia, blue-and-white porcelain is bound to be one of the cultural elements that spring to mind, and this is the main reason why “Radiating Hues of Blue on White” is one of the inaugural exhibitions of the Southern Branch of the National Palace Museum (NPM). But of course, another important reason is that the NPM’s collection of Ming dynasty blue-and-white porcelain enjoys acclaim across the world. Chinese white porcelain made its way to Western Asia in the 7th century. Although that region did not produce porcelain clay, tin-glazed replicas were made, and the pottery was decorated with blue patterns using cobalt oxide ink. This type of blue-and-white pottery wares could also be found in Tang dynasty kilns in China, but they were discontinued when foreign glaze became hard to acquire. In the mid-14th century, foreign pigments were introduced to Jingdezhen, the porcelain capital of China, and the magnificent Yuan dynasty underglaze blue porcelain was born. This type of porcelain would continue to be produced at imperial kilns during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and through Chinese emperors’ bestowment and gifting, underglaze blue porcelain wares became treasured items in imperial courts across Asia. Neighboring countries such as Korea, Vietnam, and Turkey also set up imperial kilns to produce blue-and-white pottery, and many of their decorative patterns bore clear marks of Chinese influence. When Europeans arrived in Asia, they were enchanted by the beauty of Asian blue-and-white porcelain, so they started to fire European-style blue-and-white vessels that had a strong Asian flavor. In the complex history of the development of blue-and-white porcelain, the multi-directional circulation and mutual inspiration during different periods gave rise to a globalized aesthetics. The Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain that was produced at imperial kilns occupies an important global position. Imperial kilns were not set up for trade, but the pieces they produced were highly prized by foreign nations who came to pay tribute in exchange for gifts of imperial underglaze porcelain. Exquisite quality is what sets apart Ming dynasty blue-and-white porcelain. The Ming Court spared no expense and used masses of state funds to enlist craftsmen to produce great quantities of blue-and-white porcelain wares under rigorous quality control. As gifts to other nations, many of the porcelain wares took their shapes from Central Asian metal vessels, with decorative patterns incorporating exotic elements. Ming dynasty court painters participated in the design of decorative patterns, and the ink used was often made from Central Asian minerals, so the porcelain wares were a combination of pan-Asian elements. The Ming Court knew that blue-and-white porcelain was able to follow court specifications, and Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain works provide a glimpse into the aspirations and religious faiths of successive emperors. For example, the five-clawed dragon is the symbol of imperial power; the cranes and immortals reflect the Jiajing Emperor’s Daoist faith; the Tibetan mantras indicate a close relationship between the Ming Court and Tibetan Buddhism, while the Arabic scripts are the prayers of the Zhengde Emperor. The different blue inks made the underglaze blue porcelain of the Yongle and Xuande periods look like splash ink paintings with a free and unrestrained style; the lighter-colored underglaze blue porcelain of the Chenghua reign is as elegant as sketches by the literati; the extravagantly bright underglaze porcelain of the Jiajing and Wanli periods is like the transformational school of painting. This exhibition groups Chinese porcelain works into three sections, arranged chronologically (Hongwu to Xuande periods, Zhengtong to Zhengde periods, and Jiajing reign to the end of the Ming dynasty), to illustrate how they developed during the Ming dynasty and how they incorporated elements from other Asian civilizations. In addition, the exhibition contains a fourth section displaying blue-and-white porcelain from other parts of Asia, including Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and Persia. While works from these countries were influenced by Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain, they developed different styles and contributed to the diversity of the blue-and-white aesthetics. With the exception of its Chinese porcelain, the NPM’s Asian porcelain collection is still in the process of acquisition, but it is already sufficient to illustrate an Asian world joined together by blue-and-white porcelain during the Ming dynasty. The exhibition is curated by Tsai Mei-fen, Chief Curator of the Department of Antiquities, and Weng Yu-wen, Assistant Curator of the Department of the Southern Branch Affairs. Yu-wen was responsible for selecting exhibits and writing labels and introductory texts, which were then revised and approved by the chief curator. Both curators contributed a scholarly article—Tsai’s “Radiating Hues of Blue and White: Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Porcelains in the National Palace Museum Collection” and Weng’s “Asian Blue-and-white Porcelain During the Ming Dynasty”—to give the catalogue more theoretical depth. “Radiating Hues of Blue on White” is the very first blue-and-white porcelain exhibition to feature the comprehensive NPM Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain collection. It also uses blue-and-white porcelain as a common thread to illustrate cultural exchange in Asia. Originating in China, underglaze blue porcelain enjoys widespread popularity across the world and has had far-reaching influence. The refined translucent quality in the porcelain body and the sophisticated blue decorative patterning make this porcelain a byword for luxury and a superb demonstration of the art of living.

Radiating Hues of Blue and White: Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Porcelains in the National Palace Museum Collection Cultures receive new impetus by interacting with each other. In Asia, we have witnessed many encounters, cross-fertilizations, borrowings, and re-creations between arts and cultures, and underglaze blue porcelain is a prime example. When Europeans think of Asia, blue-and-white porcelain is bound to be one of the cultural elements that spring to mind, and this is the main reason why “Radiating Hues of Blue on White” is one of the inaugural exhibitions of the Southern Branch of the National Palace Museum (NPM). But of course, another important reason is that the NPM’s collection of Ming dynasty blue-and-white porcelain enjoys acclaim across the world. Chinese white porcelain made its way to Western Asia in the 7th century. Although that region did not produce porcelain clay, tin-glazed replicas were made, and the pottery was decorated with blue patterns using cobalt oxide ink. This type of blue-and-white pottery wares could also be found in Tang dynasty kilns in China, but they were discontinued when foreign glaze became hard to acquire. In the mid-14th century, foreign pigments were introduced to Jingdezhen, the porcelain capital of China, and the magnificent Yuan dynasty underglaze blue porcelain was born. This type of porcelain would continue to be produced at imperial kilns during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and through Chinese emperors’ bestowment and gifting, underglaze blue porcelain wares became treasured items in imperial courts across Asia. Neighboring countries such as Korea, Vietnam, and Turkey also set up imperial kilns to produce blue-and-white pottery, and many of their decorative patterns bore clear marks of Chinese influence. When Europeans arrived in Asia, they were enchanted by the beauty of Asian blue-and-white porcelain, so they started to fire European-style blue-and-white vessels that had a strong Asian flavor. In the complex history of the development of blue-and-white porcelain, the multi-directional circulation and mutual inspiration during different periods gave rise to a globalized aesthetics. The Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain that was produced at imperial kilns occupies an important global position. Imperial kilns were not set up for trade, but the pieces they produced were highly prized by foreign nations who came to pay tribute in exchange for gifts of imperial underglaze porcelain. Exquisite quality is what sets apart Ming dynasty blue-and-white porcelain. The Ming Court spared no expense and used masses of state funds to enlist craftsmen to produce great quantities of blue-and-white porcelain wares under rigorous quality control. As gifts to other nations, many of the porcelain wares took their shapes from Central Asian metal vessels, with decorative patterns incorporating exotic elements. Ming dynasty court painters participated in the design of decorative patterns, and the ink used was often made from Central Asian minerals, so the porcelain wares were a combination of pan-Asian elements. The Ming Court knew that blue-and-white porcelain was able to follow court specifications, and Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain works provide a glimpse into the aspirations and religious faiths of successive emperors. For example, the five-clawed dragon is the symbol of imperial power; the cranes and immortals reflect the Jiajing Emperor’s Daoist faith; the Tibetan mantras indicate a close relationship between the Ming Court and Tibetan Buddhism, while the Arabic scripts are the prayers of the Zhengde Emperor. The different blue inks made the underglaze blue porcelain of the Yongle and Xuande periods look like splash ink paintings with a free and unrestrained style; the lighter-colored underglaze blue porcelain of the Chenghua reign is as elegant as sketches by the literati; the extravagantly bright underglaze porcelain of the Jiajing and Wanli periods is like the transformational school of painting. This exhibition groups Chinese porcelain works into three sections, arranged chronologically (Hongwu to Xuande periods, Zhengtong to Zhengde periods, and Jiajing reign to the end of the Ming dynasty), to illustrate how they developed during the Ming dynasty and how they incorporated elements from other Asian civilizations. In addition, the exhibition contains a fourth section displaying blue-and-white porcelain from other parts of Asia, including Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and Persia. While works from these countries were influenced by Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain, they developed different styles and contributed to the diversity of the blue-and-white aesthetics. With the exception of its Chinese porcelain, the NPM’s Asian porcelain collection is still in the process of acquisition, but it is already sufficient to illustrate an Asian world joined together by blue-and-white porcelain during the Ming dynasty. The exhibition is curated by Tsai Mei-fen, Chief Curator of the Department of Antiquities, and Weng Yu-wen, Assistant Curator of the Department of the Southern Branch Affairs. Yu-wen was responsible for selecting exhibits and writing labels and introductory texts, which were then revised and approved by the chief curator. Both curators contributed a scholarly article—Tsai’s “Radiating Hues of Blue and White: Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Porcelains in the National Palace Museum Collection” and Weng’s “Asian Blue-and-white Porcelain During the Ming Dynasty”—to give the catalogue more theoretical depth. “Radiating Hues of Blue on White” is the very first blue-and-white porcelain exhibition to feature the comprehensive NPM Ming dynasty underglaze blue porcelain collection. It also uses blue-and-white porcelain as a common thread to illustrate cultural exchange in Asia. Originating in China, underglaze blue porcelain enjoys widespread popularity across the world and has had far-reaching influence. The refined translucent quality in the porcelain body and the sophisticated blue decorative patterning make this porcelain a byword for luxury and a superb demonstration of the art of living.

主題書展

更多

主題書展

更多書展今日66折

您曾經瀏覽過的商品

購物須知

為了保護您的權益,「三民網路書店」提供會員七日商品鑑賞期(收到商品為起始日)。

若要辦理退貨,請在商品鑑賞期內寄回,且商品必須是全新狀態與完整包裝(商品、附件、發票、隨貨贈品等)否則恕不接受退貨。